1. Introduction

The literature has focused on many aspects of the sharecropping contract, including anthropological, legal, economic and historical. Sharecropping is a specific form of land management that links the landowner and the tenant1 (sharecropper) contractually, providing the use of a plot of land, and in some cases a rural house. The peculiarity of the contract lies in the subdivision of the product in variable quotas between landowner and sharecropper (Federico, 2006). This specific case has a global span, with a variety of contractual clauses that may include different product shares and the use of capital by the signing parties. A general classification of this form of land tenure is infeasible, given that there may be significant differences within a single nation. In 19th century Europe, sharecropping was more widespread in the Mediterranean area (Biagioli, 2013): Italy (mezzadria), France (métayage), and Spain (aparceria and masoveria in the Catalan area).

Some historians and economists have a negative opinion of this specific agrarian contract, while others are optimistic. According to Marshall (1920), sharecropping brought inevitable inefficiency, resulting in a decline in agricultural output and yields, and creating an obstacle for technical progress. Before Marshall, physiocrats had argued that metayage should be replaced by a form of capitalism that transformed and modernized agriculture through significant investments by owners and salaried work (Biagioli, 2013). There were, however, those such as John Stuart Mill (1871) who thought that the criticism of sharecropping was excessive. The idea of a contract resistant to change survived over time. From these positions, studies flourished which began to speak negatively about sharecropping. Emilio Sereni (1947) saw this contract as a feudal remnant in which there was disproportionate cultivation of wheat and excessive employment of labour (Cohen & Galassi, 1996). Moreover, sharecropping presented a negative correlation to monitoring costs (Alston & Higghs, 1982).

However, significant studies have changed this approach to the problem. In particular, those of Cheung (1969) analysed the relationship between tenant and owner, Stiglitz (1974) focused on the question of risk, and Hoffman (1982, 1984, 1996) on operating costs. From this background, scholars have recently reviewed previous studies that considered sharecropping as a backward and inefficient institution (Newbery, 1975; Winters, 1978; Bray & Robertson, 1980; Cohen & Galassi, 1990; Emigh, 1997; Carmona & Simpson, 1999, 2007; Ackerberg & Botticini, 2000, 2002; Garrido, 2017). Answers to macro questions can be found by revisiting what the international scientific debate has produced by focusing on the farm dimension. It is essential to point out that the history of agrarian farms can be utilized for general analysis of agricultural history (Galassi & Zamagni, 1993). As Giovanni Federico (1984) wrote, there are two methodological approaches to the study of peasant farms: an anthropological one in which society is studied with non-economic categories, and an economic one in which specific aspects of the agricultural sector are addressed using political economic tools. In agreement with Federico (1984), the latter appears more applicable to the analysis of 19th century Italy.

This study aims to place itself within the debate over the backwardness of sharecropping, specifically in its micro dimension, by measuring the degree and capacity of response to the exogenous shocks of the Tuscan (Italy) fattoria system2 in the second half of the 19th century. Particular attention will be paid to the 1880s to see how a sharecropping territory was able to respond to the arrival of American grains in Europe. During this time, there was a greater supply of cereals than demand, and foreign cereals began to arrive in Europe at lower prices, which created trouble for European wheat production. From a similar perspective, it is interesting to observe what occurred in the Italian countryside, given that the Italian agricultural economy was heavily based on wheat. It is significant to study sharecropping during “shocks” also because the sharecropping contract was considered a means of attracting farmers in times of crisis.

The research was conducted through an analytical study of accounting records by enriching the type of economic variables compared to previous research (Ciuffoletti, 1975, 1980, 1986; Galassi, 1986, 1987; Biagioli, 2000); the farm is an important accounting laboratory (Giradeau, 2017). Studying the accounting structure can help to acquire qualitative variables to verify the general conditions of an agricultural system. The methodological approach to farm accounting has led to important results for Spain (Pérez Picazo, 1991; Garrabou, Saguer & Sala, 1993; Garrabou et al., 1995; Garrabou, Planas & Saguer, 2001, 2012; Pascual, 2000; Lana, 2003; Planas & Sauger, 2005).

The work is notable because the fattoria system differentiates the Tuscan case from the others studied in Europe, both for the size of the farms and, in particular, because the large owners possessed farms in a variety of areas in the region. This allows for broader comparative analysis in terms of soil conformation and crop types. The relevance of this study lies in the attention paid to a fattoria located in the border area between the provinces of Florence and Siena not yet studied by the literature, thus expanding the survey sample to cover all of the agricultural regions in the two provinces. It is also significant because in 1835 the area had a limited presence of vines and olive trees, a peculiarity that makes the fattoria a particularly interesting case study in which to measure the degree of inversion in production in the second half of the 19th century compared to the fattorie already studied in areas with a high incidence of vines (Galassi, 1986, 1987; Biagioli, 2000). However, the most essential aspect is that, compared to Galassi (1986, 1987, 1993, 1996), who has studied aspects mainly related to the production and productivity of factors, this study also reconstructs the expenses for crops and the sales market.

The evolution of wheat and corn production, as well as oil and wine, can be estimated from accounting records dating from the period of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany to the process of unification and consolidation of the new State. Those records also provide information on the market trend of sales of the main products of Canonica (wheat, corn, wine and oil) from the pre-unification period to 1889 (when the series of accounting records ends). Moreover, they reconstructed the evolution of sharecropper living standards in the same timeframe in order to propose a global vision of the productive and social conditions of the fattoria during a period of economic stress. This research enables the acquisition of new elements on the evolution of Tuscan agriculture in the post-unification years, which are particularly meaningful considering the difficulty in obtaining data on a municipal scale and the precarious reliability of the statistics. Furthermore, this work enriches the literature on Tuscan fattorie in the second half of the 19th century, with the attainment of significant information on investments by a large property that appeared unwilling to invest capital in agriculture rather than safer treasury bonds (Galassi, 1986). An attempt has been made to demonstrate how Tuscan sharecropping presented elements of dynamism through its ability to adopt strategies that allowed it to follow agricultural market trends.

This paper tests the hypothesis by Fenoaltea (2006) that the years of the cereal crisis were in fact a period of growth and specialization for agriculture. Going back to the 1880s is crucial in order to attempt to respond, at a micro level, to some of the questions posed by historiography. To these, we have tried to respond at a macro level (Fenoaltea, 2006; Zanibelli, 2022a). According to Pescosolido (1998), the decrease in the price of wheat should have led to a decrease in food consumption, while according to Zamagni (1981), there should have been social unrest and emigration. This would have led in turn to social tensions, and ultimately, considerable migratory flow. Castronovo (1995) also sees these years as critical. While Fenoaltea (2006) has provided some important macro responses, it is also essential to attempt to reconstruct what happened inside businesses. This is predominantly because the latter makes it possible to enrich the debate over some specific points. Fenoaltea (2006), for instance, points out the difficulty in finding data such as agricultural wages. Analysing the micro case is imperative because it allows us to verify what has been shown on a national scale with annual data, thus significantly enriching the historiographical debate regarding the years of deflation.

The article is organized as follows: Section II presents a politico-economic study of Tuscan sharecropping. This section also describes the accounting documentation used and its importance for fattoria’s governance. Section III presents data on the size of Canonica’s poderi and its sharecroppers. Section IV analyses the evolution of Canonica’s agricultural production, the fattoria’s income, and the debt of sharecroppers in the same period. Finally, a number of conclusions are drawn.

2. Sharecropping in Italy, 1881-1931

With regard to the Italian case we can confirm that sharecropping, despite being present in almost all of the Peninsula provinces, was concentrated mainly in the central regions and especially in Tuscany. In the various regions, sharecropping took on different characteristics, from the traditional Tuscan sharecropping (MAIC, 1891; Federico, 2006; Biagioli & Pazzagli, 2013) in which a strong bond tied the sharecropper to the land and the dwelling, to particular dissimilarities regarding the contract and its application localized in the south (Russo, 2013). In Sicily, for example, the agreements were non-exclusive, and sharecroppers did not reside on the farm. Thus, there was no strong link between the land and the sharecropping family. In Campania, however, the share of subdivision of wine was based on the quality of the product.

Although the planned duration of the contract was one year, this ended up being much longer, as confirmed by the accounting records of this research. The study of population censuses and other statistical sources has made it possible to reconstruct the evolution of sharecropping in the Italian peninsula from 1861 to 1931. It is estimated (1861) that roughly half of the agricultural workers in the central regions were sharecroppers. According to the first General Census of the Population of Italy, 34% of the agricultural population were sharecroppers in Modena, Reggio and Massa, 57% in Romagna, 71% in Marche, 38% in Umbria and 40% in Tuscany (MAIC, 1863). As can be seen in Table 1, from 1881 to 1931, the presence of this contract is located in the central regions (MAIC, 1882; ISTAT, 1935a)3. It is interesting to observe the growth of sharecropping in all of the regions from 1881 to 1931, particularly from 1881 to 1911. This would make it possible to hypothesize a diffusion of this contract during the exogenous shocks, confirming the importance of analysing the productive system of the Tuscan sharecropping. The significance of this contract was taken into consideration for the entire central area of the Italian peninsula.

TABLE 1

Percentage of land under sharecropping in Italian regions

| Regions | 1881 | 1911 | 1931 |

|---|---|---|---|

| North | |||

| Piedmont | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Liguria | 9 | 14 | 12 |

| Lombardy | 14 | 21 | 13 |

| Veneto | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| Center | |||

| Emilia | 30 | 33 | 34 |

| Tuscany | 46 | 57 | 59 |

| Marche | 59 | 60 | 65 |

| Umbria | 20 | 50 | 58 |

| Lazio | 9 | 16 | 22 |

| South and Island | |||

| Abruzzi and Molise | 11 | 15 | 17 |

| Campania | 6 | 11 | 6 |

| Apulia | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Basilicata | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Calabria | 4 | 12 | 16 |

| Sicily | 5 | 9 | 19 |

| Sardinia | 7 | 5 | 11 |

| North | 9 | 13 | 12 |

| Center | 39 | 50 | 54 |

| South | 6 | 9 | 13 |

| Italy | 13 | 20 | 22 |

Source: own processing from MAIC (1882) and ISTAT (1935a). Values are expressed in% of workers (man).

2.1. Tuscan Sharecropping: characteristics, location, and accounting system

In Tuscany, the productive sharecropping structure revolved around the podere (Biagioli, 2000). The sum of these units formed the fattoria (Ciuffoletti, 1986; Galassi, 1986, 1987; Biagioli, 2000; Zanibelli, 2019)4, where corporate governance was planned and administered. The production was divided in half between sharecropper and landlords, the latter’s share being called parte dominicale. This term refers to the part of the production that went to the landowner, who kept the best part for himself (Biagioli, 2000). The landowner entrusted the control of the company to an agent called fattore, who had specific agricultural knowledge and was the liaison between sharecropper and landlord (Cianferoni, 1973; Biagioli, 2000). This supervisory role was particularly significant because, unlike the Spanish case, it required a fair level of knowledge of agricultural techniques (Planas & Sauger, 2005; Pazzagli, 2008).

According to Biagioli (2013), the Tuscan mezzadria shared similarities with French metayage and Catalan masoveria. The factors that distinguished them from other contracts include: a) agreements essentially based on Roman law: sharecroppers were bound to land improvement works, while owners had to make investments before the establishment of the family; b) investment in livestock and agricultural tools in the Catalan masoveria at the worker’s expense, although landowners occasionally provided grain for sowing: in France and Italy, the landowner was involved in the provision of goods, though in some areas the livestock had to be provided by sharecroppers (in Tuscany, seeds were supplied jointly, while cattle were supplied by the owner); c) production units based on the policoltura of wheat, oil and wine; d) an obligation on the part of the worker’s family to cultivate the land received in concession and the prohibition from cultivating any other, additional land.

Regarding the spatial distribution of this contract in Tuscany, Rogari (1998, 2002, 2009) pointed out that during Unification, sharecropping occupied 800,000 hectares, approximately 1/3 of the Tuscan territory, and that 63% of the population of this area lived under this contract. Rogari (2009), reporting a study by Bellicini (1989), revealed that the incidence of sharecropping increased between 1830 and 1930. The 1930 Census of Agriculture shows a slight increase in the relevance of sharecropping, which accounted for 40% of the agrarian population (ISTAT, 1935a). In three agricultural areas of Tuscany, the prevalence of sharecropping was even greater: 51% in the hills, followed by 38% in the lowland area, and the lowest, recorded at 21%, in the mountains (ISTAT, 1935b). Hills provided rich land for vines and olive trees, though the introduction of agricultural machinery was difficult (Galassi, 1986). Shifting the focus to the provincial scale (ISTAT, 1935b), in 1930 sharecropping was predominantly concentrated in the provinces of Florence and Siena (60%) followed by 54% in Arezzo. The ratios in the other provinces were substantially lower5. The extensive presence of sharecropper production units in Florence and Siena was due to the significant number of large landholdings (fattorie). This confirms that most of the population in the two provinces (Siena and Florence) lived under sharecropping (Detti & Pazzagli, 2000; Zanibelli, 2022b).

Some scholars analysed Tuscan sharecropping from a negative position (Sereni, 1947, 2016; Giorgetti, 1974; Pazzagli, 1973, 1979), framing it as a backward contract unwilling to change, despite no incompatibility being detected between sharecropping and capitalist development (Lehman, 1984). The political climate of Italy after Second World War, in which the Marxist thesis on the inequity of sharecropping, due to the extraction of surplus labor in feudal working environments, deeply conditioned the historiography developed around Sereni’s positions (1947). Also, one of the issues was that one position looked at the single parts of the contract and not at both, without considering that one part could provide what the other lacked (Reid, 1973). The optimistic view began to gain ground with the studies on the fattoria system by Mirri (1970) and Biagioli (1970), who brought to light the importance of focusing attention on the farm dimension, thus beginning a national debate on the issue; particularly on the relevance of accounting (Coppola, 1983; Galassi & Zamagni, 1993). Since the global explications not allow production and productivity to be measured, it was not possible to carry out analyses on historical series or measure the real relationship between landowner and sharecropper (Herring, 1978; Robertson, 1987).

The economic structure of Tuscan fattorie required proper and extensive accounting-administrative documentation: the Libri di Fattoria (Saldi). These documents are crucial for accounting (Mussari & Magliacani, 2007) because they provide insight into the development of production and the economic relations between landowner and sharecropper (Cianferoni, 1973; Poni, 1978; Biagioli, 2000). Furthermore, they allow for the detection of important variables such as production, productivity, expenses for fertilizers and new crops, and poderi accounting (Cianferoni, 1973).

The peculiarity of the Tuscan case lies in the presence of accurate accounting structures, realized through a pre-established scheme (Tantini, 1852), which enables the measurement of the qualitative evolution of the documentation in order to relate it to the economic performance of the fattoria. In addition, the accounting books offer the opportunity to carry out comparative analyses between various fattorie with homogeneous series. In this perspective, accounting books become useful tools for corporate governance to respond to exogenous shocks.

3. The Canonica fattoria of Certaldo: location, size and structure of the agrarian population

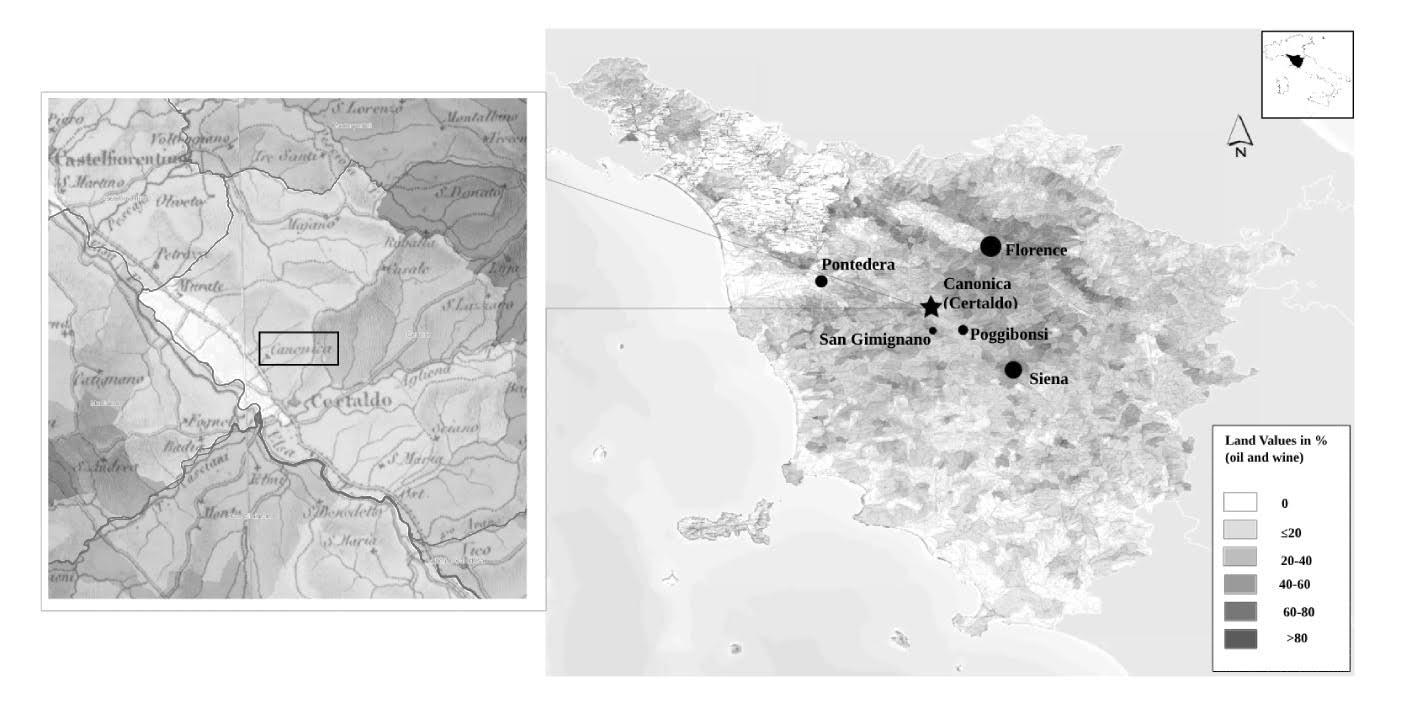

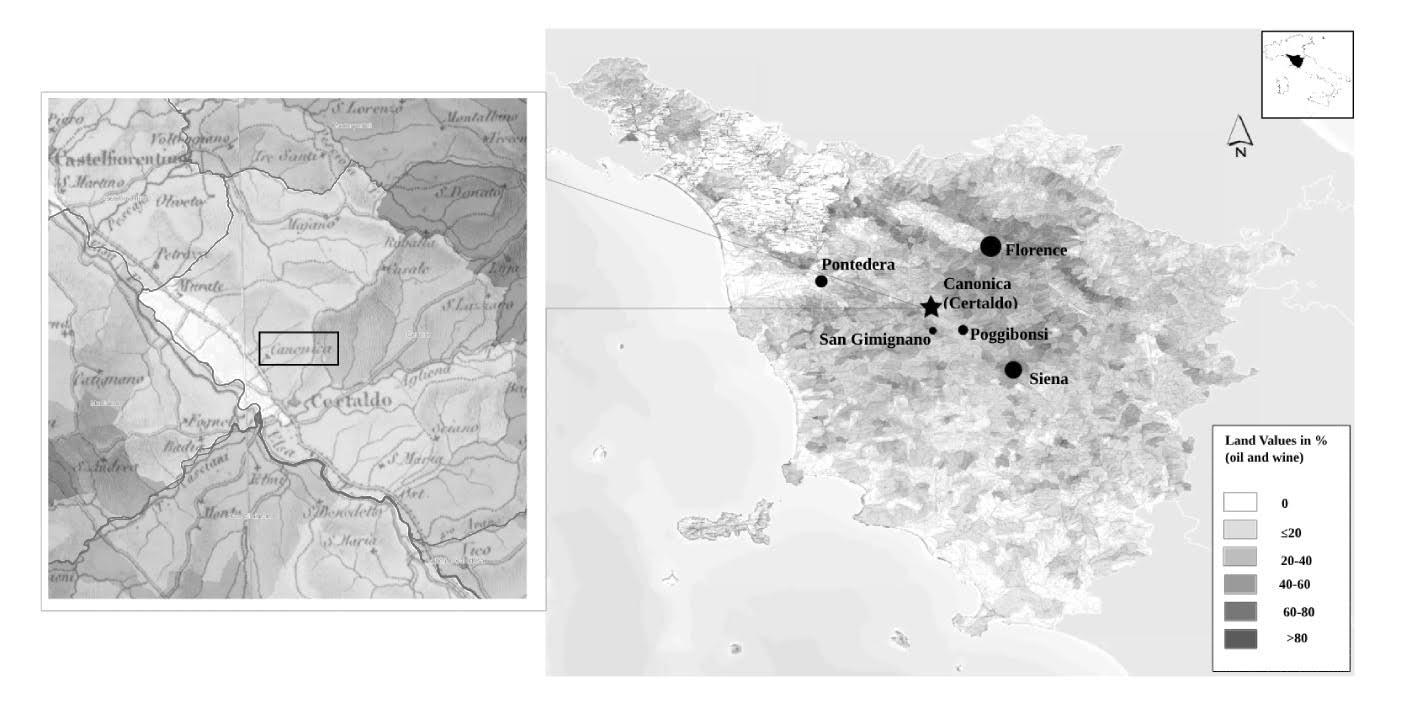

As anticipated, in this research we will focus on Tuscany (Italy), specifically the area of Certaldo, located on the border between Siena and Florence (Fig. 1). This is a particularly key municipality because it is situated in a border area, which makes it possible to analyse the structural or non-structural dependence of the agricultural sector on Siena and Florence. In addition, Certaldo’s agricultural population was mainly formed by sharecroppers (Azzari, 1982).

FIGURE 1

The localization of Canonica in Tuscany

Source: our own processing with GIS. The cartogram also shows the different markets where the fattoria’s products were sold. The municipalities are represented on a scale of size per number of inhabitants.

The fattoria studied is the Canonica6, the property which extended over 647 hectares from 1858 to 1868 (Zanibelli, 2019). In the pre-unitary period, Canonica did not show specialization towards vine cultivation, thus showing a predominance of arable land7. The map also shows the main sales markets of the fattoria and the cities of Siena and Florence, to facilitate the location of the area studied. Initially, Canonica was divided into 25 poderi, though later sub-divided into more. Before the process of national unification, the average size of the podere was 26 hectares (Fig. A1)8. The data indicates how the owners of the company likely fractionalized units, as in other areas of Tuscany (Ridolfi, 1858). The community of Certaldo covered 7,396 hectares9, of which approximately 97% corresponded to the agrarian and forest area10. Canonica’s fattoria occupied around 9% of this share.

The time series of production and value have been reconstructed through the accounting documentation (Saldi)11. An initial, qualitative approach to the source has revealed that the accounting entries maintained a high qualitative level during the period observed. No drop in the quality of accounting was detected during the period of exogenous shock (1880s). The registers have a homogeneous structure that tends to be preserved over time, according to the classical scheme of Tuscan sharecropping (Tantini, 1852). This first study of archival source quality has provided evidence of the attention that the property owner and farm agent paid to keeping the accounts, by offering a first indicator of the structural well-being of the farm. The analysis focuses on wheat, corn, oil and wine as indicative of the sharecropping economy. The fattoria also produced most of the minor cereals and legumes. The reconstruction of the time series on production has also allowed us to measure the trend of the sale of products, the income of the fattoria, and sharecropper debt. The archival documentation supplies insight into production factors, including capital (land rent), work and land (corresponding to the podere dimension understood as arable land).

Population analysis is essential because it enables the reconstruction of the size of households and investigation into the changing living conditions of sharecroppers during economic shock12. Analysis of the Canonica population was detected through the specific register containing the agricultural population of the fattoria available from 1870 to 1874. This data is relevant because not all fattorie had special sharecropper family registers.

During the above-mentioned timeframe, there was a migration of 11 men and 13 women. The numbers are of little importance, considering that the authorization of the landowner was necessary in order to leave the podere. The women left the house to marry, and the men most likely took over other poderi of other fattorie. During the period between 1870 and 1874 (Table A1), the population of Canonica was 250 inhabitants, of which 108 were men (43%), 88 women (35%) and 55 children (22%)13. The average number of men, women and children per household was 4, 3 and 2, respectively, making the average household size 9. The Libretti Colonici have enabled the detection of an average lifespan of under 50 years. Canonica had 152 work units spread over 650 hectares14.

From the accounting records, we were also able to reconstruct the evolution of the farm supervisory labourers. This information is valuable because it allowed us to detect the effect of supervision policies on the economic performance of the fattoria. In the period observed, three fattori directed Canonica: Anton Maria Pacini from 1858 to 1864; Giovanni Pacini from 1865 to 1881; and Roberto Buracchi from 1882 to 1889.

4. The fattoria’s reaction to the exogenous shock: production strategy, market and sharecropper living conditions

This section reports the results achieved through the analytical study of the fattoria’s accounting records15. It is organized as follows: a description of the movement of farm price trends in management and production costs, the change in the product structure and market, and lastly, the evolution of sharecropper living conditions to provide a general picture of economic conditions in Canonica during the period of economic shocks. International macroeconomic changes heavily influenced an agricultural economy such as Italy’s, strongly centered on wheat, by promoting processes of changes in production in favor of commercial products (oil and wine), at the expense of cereals (Fenoaltea, 2006; Zanibelli, 2022a). The winds of change also arrived in sharecropping areas such as Tuscany. A similar trend occurred in other countries in the Mediterranean area with a high presence of sharecroppers, such as Spain, albeit in different ways (Simpson, 2001; Serrano, Sabaté & Fillat, 2021). Although the productive system of the Tuscan farm was based on a rational distribution of crops, wheat also played a key role in the production structure, as in other Mediterranean economies (Serrano, Sabaté & Fillat, 2021). Although an exogenous shock of such magnitude could have affected the economy of the Tuscan countryside, deflation brought with it a propulsive boost to major commercial products, and the fattoria was able to respond to these macroeconomic changes by preserving its economic performance (Fig. A2). Even in Canonica’s sale prices during the cereal crisis there was a decrease in the relative price of wheat and wine. Values increased after the introduction of protectionist measures (1887). There is a difference between the trend of provincial and farm values in 1885, when Canonica returned to producing more wheat. Although the accounting records end abruptly in 1889, data from the last two years of the time series are in line with provincial figures.

The changes caused by deflation and the arrival of phylloxera in France led to the development of new market prospects for Tuscan wine in other Italian regions. The resulting growth of the wine sector was not entirely destined for export to foreign countries (Galassi, 1986). Environmental and macro-economic conditions were a contributing factor to initial investments in Tuscan viticulture of the 1870s. Landowners, seeing what was happening in France, were incentivized to continue expanding this crop. Investing in wine also entailed increased costs of management, control and “improvement works”, understood as all those actions put in place to improve crops in the long run. Canonica showed itself to be attentive to international changes, and for this reason the expenditure on fertilizers (manure) and sulfur rose during the 1880s. Landowners’ willingness to invest in production improvements, in particular for wine (Fig. A3), was demonstrated by the introduction of new crops during the 1870s. The propensity to invest was also observed for other big farms, such as in Tuscany (Galassi, 1986, 1987) and Lazio (Felisini, 2019). It emerges that the enlightened nobility was interested in improving the production systems of their large agricultural farms. As for Canonica, these resources found appropriate allocation through proper use by qualified production control figures (fattori) who knew how to properly manage the use of production factors. In the fattoria, investments continued even in the first years of the crisis, the trend of which reversed beginning in 1883 and then stabilized under the protectionist laws of 1887. The property investment policies were in line with the provincial ones (MAIC, 1881). After this measure, the values returned to the same level as the years prior to the crisis, when there was a new tendency to favor the cultivation of wheat thanks to rising cereal prices.

Until the 1880s, wheat and corn occupied the largest annual share of the total value of the fattoria’s production (Table 2). The cereal output remained constant until the 1880s, and during the crisis there was also substantial improvement in wheat and corn production (Fig. A4). The quantity then began to drop when protectionist measures were enforced in 1887. Canonica’s values are not in line with those of other Tuscan farms (Galassi, 1986, 1987, 1996), where no similar trend is observed. The fattoria’s good results are likely to be found in the fact that a decrease in the cultivated area did not follow a decline in production during the crisis, thanks to the increase in yields (Fig. A5).

With regard to commercial products after the 1880s, the wine share, which constituted the majority, increased significantly16. The growth of wine output continued in the period following the beginning of enforcement of the protectionist measures of 1887, when production stabilized and returned to its pre-crisis level. Wine production grew until the 1870s, when it stabilized. From the 1880s on, production grew, with peaks between 1882 and 1883 (Table A2). Considering that four years must pass between the planting and production of the vine, the increase in production in the 1880s was due to the investments made in the same timeframe. This is also confirmed by what emerged at the aggregate level, where the similarity of Canonica’s values with the general values for the province of Siena can be observed (Table A3). The growth of wine production was closely related to both that of relative provincial and fattoria prices. In the years 1887-89, production stabilized and returned to the numbers before the crisis. For these years, the trend was similar to one of the fattorie analysed by Galassi (1986, 1987), located in the province of Siena. Oil occupied a relevant portion during the period from 1858 to 1863. Subsequently, its share dropped to a minimum, and in later years occupied a smaller part of the total farm production. Moreover, for this type of product, the relevance of the effects of atmospheric agents must also be taken into account, as they play a significant role in production17. Between 1858 and 1889, production declined until the end of the 1870s, when the trend reversed until 1887 (the year protectionist measures went into effect).

TABLE 2

Percentage share of wheat, wine, oil and corn in total production value, 1858-89

| Period | Wheat | Wine | Oil | Corn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1858-64 | 36 | 12 | 38 | 15 |

| 1865-69 | 37 | 44 | 6 | 13 |

| 1870-74 | 46 | 29 | 5 | 20 |

| 1875-79 | 42 | 28 | 4 | 29 |

| 1880-84 | 32 | 38 | 3 | 26 |

| 1885-89 | 33 | 39 | 3 | 25 |

Source: our own processing from AS SI, Postunitario, Azienda la Canonica, Amministrazione. Values in%.

FIGURE 2

Total production value and agricultural income of Canonica. 1858-89

Source: our own processing from AS SI, Postunitario, Azienda la Canonica, Amministrazione.

The crop transition towards wine preserved the fattoria from the fluctuation of the relative wheat/wine price, by registering a growth in the output values and income (Fig. 2). This is due to the increase in the production and sale of wine, considering that with the consolidation of protectionist policies in support of wheat, the value falls below the average for the 1858-89 period.

The strong economic performance of the fattoria must also be analysed in relation to the management and control system based on the figure of the fattore: the economic growth of Canonica commences with Giovanni Pacini’s management, and becomes solid with that of Roberto Buracchi, thus showing a propensity of the landowner to invest in human capital with managerial skills.

Production changes also caused a switch in the market for Canonica products, with a decrease in cereal sales and an expansion of commercial products. As Giuliana Biagioli (2000) wrote, the sharecropping market in the first half of the 19th century was distributed in proximity to the fattoria. For the Ricasoli fattorie located in the Chianti, the goods were easier to sell on the Siena market than in Florence due to the problem of transportation costs. Quality wine arrived on the Florence market and was sold in the landowner’s cellar. Transportation costs were absorbed by the presence of wealthy people in Florence who guaranteed the purchase of the product (Biagioli, 2000).

The data shows how the fattoria had its own market space, in particular thanks to its location on the border between the two provinces of Siena and Florence18. The location of the fattoria, however, also opened it up to other markets along the Siena-Empoli route to reach Pontedera (Fig. 1). The railway also played an important role. Cereals, wine and oil had different markets and sales processes (Biagioli, 2000). The cereals were consumed nearby, not only in the municipalities of Poggibonsi, San Gimignano and Certaldo, but also in Siena. The accounting documents do not allow for the detection of transportation costs, even though in some registers, it is reported that a portion of the goods was collected by the merchants at the fattoria. Using the data from Biagioli (2000), a transport cost of 5% for wheat to Siena can be hypothesized. The same values were used to estimate the trend in transportation costs, considering that this occurred predominantly with wagons19. The decrease in transportation costs may have opened fattoria products to new markets, thus increasing the opportunities for grain sales outside the traditional circuits. In some cases, these products were also sold in greater quantities than in the parte dominicale. As far as wine is concerned, the great demand also led to the sale of part of that of the sharecroppers, who obtained benefits from this, among which was reducing the debt with the owner. Sales price trends revealed how the fattoria market was more closely linked to the Siena market, based on proximity, than Florence, which had an international dimension (Fig. A2).

Changes in the fattoria market, particularly the decrease in wheat sales (Fig. A6), also greatly affected the living conditions of sharecroppers. The debt was mainly derived from the wheat loan, so a decrease in the price of cereal favored a reduction in sharecropper monetary debt (Biagioli, 2000). This is particularly relevant because the sharecroppers were always heavily indebted to the landowner, and therefore obliged to repay the debt with other types of services (such as improvement work in the fields) because landlords supplied the only source of credit to which the sharecroppers had access.

The crisis of the 1880s seems to have led to improvements in living conditions, as the value of the debt decreased without a corresponding decrease in cereal production. If the debt decreased, it is assumed that there was consequentially an improvement in the living conditions of the peasants. For this reason, Allen’s (2001) surveys of annual caloric consumption let us estimate the trend in sharecropper wheat consumption, which subsequently lets us calculate the total share of sharecropper nutrition. Analyses conducted show that there was no shortage of cereals on the fattoria, and that the quantity available for food use increased in the 1880s, as observed in other areas of Tuscany (Biagioli, 2000). The decrease in the price of cereal led to investment in other crops, thus guaranteeing greater availability for sharecropping families, who in turn reduced their debt and improved their living conditions (Fig. 3). In 1887, the trend changed once again. The data confirm Fenoaltea’s analysis (2006). The decrease in the price of wheat brought an improvement in living conditions and wages. Essentially, there was no worsening of per capita consumption, as hypothesized at the macro level (Pescosolido, 1998), but an improvement in the amount of wheat available for food use. With the enforcement of the 1887 tariff, the situation worsened. Moreover, the structure of agricultural families remained the same over time, allowing us to assume that there were no significant agrarian migrations, as evidenced at the national level (Castronovo, 1995).

Accounting records revealed how the fattoria was able to respond to the macroeconomic changes caused by the exogenous shock by also showing a propensity for growth. Thus, the theories of backward sharecropping severely affected by the cereal crisis do not seem to be supported by this study at a fattoria level (Georgetti, 1974; Pazzagli, 1973, 1979; Sereni, 1947, 2016). The more positive view by Biagioli (2000), Mirri (1970), and Galassi (1986, 1987) of an active, dynamic sharecropping system seems to be more correct.

FIGURE 3

Wheat quantity available in addition to consumption and evolution of debt

Source: our own processing from ASS, Postunitario, Azienda la Canonica, Amministrazione.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained enrich the debate regarding Tuscan agrarian history in the post-unification period and especially during the exogenous shocks of the 1880s. In particular, four aspects emerged: the inclination of the landowner to invest, the ability of the production and accounting systems to respond to exogenous shocks, the improvement of sharecropper living conditions during the 1880s, and the fattoria’s high-quality accounting.

The elaboration of the data contained in the accounting books has enabled us to obtain significant results, thus enriching the debate over the reaction of the sharecropping system to the exogenous shocks (Galassi, 1986, 1987). The results align with the theory that sharecropping is a contract capable of adapting to changes (Winters, 1978).

The analysis of the data has brought to light how, after the 1870s (management of the fattoria of Giovanni Pacini), significant investment was made into the introduction of new crops (vines), thus making it possible to respond decisively to the fall in cereal prices during the period of deflation. Once the new crops entered production, there was an increase in sales of commercial products, mainly wine. The increase in sales was also favored by the arrival of phylloxera in France, which opened new market space for Tuscan wine in the Italian market. Observing sales performance is vital because the sharecropping structure demonstrates exceptional ability to adapt to market changes (Newbery, 1975). The resources produced by the increase in sales of wine permitted an expansion in expenditures for fertilizers, thus beginning a process of economic growth for the fattoria. The evidence of Canonica is in line with that of the province (MAIC, 1881), and also shows the erroneous perception of sharecropping as a system hostile to investments and enhancement.

The new investments brought significant improvements within the production system and allowed the production of wheat to remain high during the 1880s despite a reduction in the area cultivated. This was possible because the increased use of fertilizers caused an increment in wheat yields. Deflation led to a decrease in cereal sales, which resulted in the availability of high-quality cereals for food on the farm. This resulted in an improvement in sharecropper living standards, thus also favouring better allocation of the labour factor within the production cycle.

Landowner investments made up for the difficulties in accessing credit that smallholders would otherwise have encountered. So, the sharecropping contract allowed for significant interventions compared to other areas (Serrano, Sabaté & Fillat, 2021).

The dynamism of the fattoria is in line with that of the province of Siena, where the production of commercial products (oil and wine) continued to grow even after the introduction of protectionist tariffs in 1887. This fact confirms the significance of agricultural institutions (Accademia dei Georgofili and Comizi Agrari) in the growth of human capital and the transmission of agricultural and accounting knowledge (Bertini, 2001; Zanibelli, 2022b). This need be explored in order to understand the successful performance of the Canonica.

To achieve these results, clear and outlined strategic planning of the farm production system was necessary by the property owner through the work of the fattore. Developing a proper response strategy to economic shocks also required an efficient administrative structure set up by the owner, in order to assist the fattore during the business planning process.

From a similar perspective, the accounting structure of the Canonica was a key element which, together with the propensity to invest by ownership, helped to respond positively to the economic shock of the 1880s. The book of Saldi was an essential tool for a proper agricultural administration because, in addition to ordering the accounts reported in the same document, it also covered all the economic activities of the farm, thus favoring strategic planning by the different agents of the farm who followed over time. As has been found during the period observed, no changes in the quality of the accounting are noticed, confirming a correlation between business performance and accounting accuracy.

Summing up, it emerges that the capacity to respond to the exogenous shock of the 1880s was due to the tendency of property owners to invest in supervisory labourers and the administrative structure of the fattoria. Landowners were also able to grasp the changes that were happening in Tuscany, in particular the introduction of new cultivations of vines and the use of more fertilizer. These operations improved production, productivity, and also sharecropper living conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank the editorial board of Historia Agraria and the anonymous reviewers whose comments made it possible to improve this paper.

References

Ackerberg, Daniel A. & Botticini, Maria Stella (2000). The Choice of Agrarian Contracts in Early Renaissance Tuscany: Risk Sharing, Moral Hazard, or Capital Market Imperfections? Explorations in Economic History, 37 (3), 241-57.

Ackerberg, Daniel A. & Botticini, Maria Stella (2002). Endogenous Matching and the Empirical Determinants of Contract Form. Journal of Political Economy, 110 (3), 564-91.

Allen, Robert C. (2001). The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War. Exploration in Economic History, (38), 411-47.

Alston, Lee J. & Higgs, Robert (1982), Contractual Mix in Southern Agriculture since the Civil War: Facts, Hypotheses and Tests. Journal of Economic History, (42), 327-53.

Azzari, Margherita (1982). Certaldo e il censimento nominativo del 1841: Un contributo alla individuazione delle condizioni professionali e patrimoniali di un comune rurale del contado fiorentino. Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, XXII (2), 179-202.

Bandettini, Pierfrancesco (1957). I prezzi sul mercato di Firenze dal 1800 al 1990. Roma: Archivio Economico dell’Unificazione Italiana.

Bellicini, Lorenzo (1989). La campagna urbanizzata: Fattorie e case coloniche nell’Italia centrale e nordorientale, in Storia dell’agricoltura italiana in età contemporanea. Venezia: Marsilio.

Bertini, Fabio (2001). Organizzazione economica e politica dell’agricoltura nel xx secolo: Cent’anni di storia del Consorzio agrario di Siena (1901-2000). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Biagioli, Giuliana (1970). Vicende dell’agricoltura del Granducato di Toscana nel secolo xix: Le fattorie di Bettino Ricasoli. In Agricoltura e sviluppo del capitalismo (pp. 148-59). Roma: Istituto Gramsci.

Biagioli, Giuliana (2000). Il modello del proprietario imprenditore nella Toscana dell’Ottocento: Bettino Ricasoli, Il patrimonio, le fattorie (vol. 1, pp. 566-66). Firenze: Olschki.

Biagioli, Giuliana (2013). Mezzadria, métayage, masoveria: Un contratto di colonia parziaria e le sue interpretazioni tra Italia, Francia e Catalogna. Proposte e Ricerche, (71), 4-29.

Biagioli, Giuliana & Pazzagli, Rossano (Eds.) (2013). Mezzadri e mezzadrie tra Toscana e Mediterraneo: Una prospettiva storica. Pisa: Felici.

Bray, Francesca A. & Robertson, A. F. (1980), Sharecropping in Kelantan, Malaysia. Research in Economic Anthropology, (3), 209-44.

Carmona, Juan & Simpson, James (1999). The “Rabassa Morta” in Catalan Viticulture: The Rise and Decline of a Long-Term Sharecropping Contract, 1670s-1920s. Journal of Economic History, 59 (2), 290-315.

Carmona, Juan & Simpson, James (2007). Why Sharecropping? Explain its Presence and Absence in Europe’s Vineyards, 1750-1950. Working Papers in Economic History. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

Castronovo, Valerio (1995). Storia economica d’Italia: Dall’Ottocento ai giorni nostri. Torino: Einaudi.

Cohen, Jon S. & Galassi, Francesco L. (1990). Sharecropping and Productivity: Feudal Residues in Italian Agriculture, 1911. The Economic History Review, 43 (4), 646-56.

Cheung, Steven N. S. (1969). The Theory of Share Tenancy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cianferoni, Reginaldo (1973). Gli antichi libri contabili delle Fattorie quali fonti della storia dell’agricoltura e dell’economia toscana: Metodi e problemi della loro utilizzazione. Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, (3), 35-63.

Ciuffoletti, Zeffiro (1975). Bettino Ricasoli fra High farming e mezzadria: La tenuta sperimentale di Barbanella in Maremma (1855-1859). Studi Storici, 16 (2), 495-522.

Ciuffoletti, Zeffiro (1980). L’introduzione delle macchine nell’agricoltura mezzadrile toscana dall’Unità al fascismo. Annali dell’Istituto Alcide Cervi, 101-120.

Ciuffoletti, Zeffiro (1986). Il sistema di fattoria in Toscana. Firenze: Centro editoriale toscano.

Coppola, Gauro (Eds.) (1983). Agricoltura e aziende agrarie nell’Italia centro-settentrionale (secoli xvi-xix). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Detti, Tommaso & Pazzagli, Carlo (2000). La struttura fondiaria del Granducato di Toscana alla fine dell’ancien régime: Un quadro d’insieme. Popolazione e storia, 1 (1-2), 15-47.

Emigh, Rebecca J. (1997). The Spread of Sharecropping in Tuscany: The Political Economy of Transaction Costs. American Sociological Review, 62 (3), 423-42.

Federico, Giovanni (1984). Azienda Contadina e autoconsumo fra antropologia ed econometria: Considerazioni metodologiche. Rivista di Storia Economica, (2), 222-68.

Federico, Giovanni (2006). The ’Real' Puzzle of Sharecropping: Why is it disappearing? Continuity and Change, 21 (2), 261-85.

Felisini, Daniela (2019). Far from the Passive Property: An Entrepreneurial Landowner in the Nineteenth Century Papal State. Business History, 64 (2), 226-38.

Fenoaltea, Stefano (2006). L’economia italiana dall’Unità alla Grande Guerra. Roma: Laterza.

Galassi, Francesco L. (1986). Stasi e sviluppo nell’agricoltura toscana 1870-1914: Primi risultati di uno studio aziendale. Rivista di storia economica, 3 (3), 304-37.

Galassi, Francesco L. (1987). Reassessing Mediterranean Agriculture: Stagnation and Growth in Tuscany. 1870-1914. Phd. thesis. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Galassi, Francesco L. (1993). Mezzadria e sviluppo tecnologico tra ‘800 e ‘900. Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, (2), 92-123.

Galassi, Francesco L. (1996). Estimating Labour Productivity in Multicropfarming: A Product-Specific Approach. Histoire & Mesure, 11 (3-4), 299-327.

Galassi, Francesco L. & Zamagni, Vera (1993). L’azienda agraria: Un problema storiografico aperto. 1860-1940. Annali Feltrinelli, (29), 3-16.

Garrabou, Ramon, Saguer, Enric & Sala, Pere (1993). Formas de gestión patrimonial y evolución de la renta a partir del análisis de contabilidades agrarias: Los patrimonios del marqués de Sentmenat en el Vallés y en Urgell (1820-1917). Noticiario de Historia Agraria, (10), 89-130.

Garrabou, Ramon, Pascual, Pere, Pujol, Josep & Saguer, Enric (1995). Potencialidad productiva y rendimientos cerealícolas en la agricultura catalana contemporánea. Noticiario de Historia Agraria, (5), 97-125.

Garrabou, Ramon, Planas, Jordi & Saguer, Enric (2001). Sharecropping and Management of Large Rural Estates in Contemporary Catalonia. Journal of Peasant Studies, 28 (3), 89-108.

Garrabou, Ramon, Planas, Jordi & Saguer, Enric (2012). The Management of Agricultural Estates in Catalonia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century. Agricultural History Review, 60 (2), 173-190.

Garrido, Samuel (2017). Sharecropping was Sometimes Efficient: Sharecropping with Compensation for Improvements in European Viticulture. The Economic History Review, 70 (3), 977-1003.

Giorgetti, Giorgio (1974). Contadini e proprietari nell’Italia moderna: Rapporti di produzione e contratti agrari dal secolo xvi ad oggi. Torino: Einaudi.

Giraudeau, Martin (2017). The Farm as an Accounting Laboratory: An Essay on the History of Accounting and Agriculture. Accounting History Review, 27 (2), 201-15.

Herring, Ronald J. (1978), Share Tenancy and Economic Efficiency: The South Asian Case. Journal of Peasant Studies, 7 (4), 225-49.

Hoffman, Philip T. (1982). Sharecropping and Investment in Agriculture in Early Modern France. The Journal of Economic History, 42 (1), 155-59.

Hoffman, Philip T. (1984). The Economic Theory of Sharecropping in Early Modern France. The Journal of Economic History, 44 (2), 309-19.

Hoffman, Philip T. (1996). Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450-1815. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Istituto Centrale di Statistica del Regno di Italia (ISTAT) (1935a). VII Censimento generale della popolazione IV: Relazione generale. Roma: Tip. Failli.

Istituto Centrale di Statistica del Regno di Italia (ISTAT) (1935b). Censimento Generale dell’Agricoltura II: Censimento delle aziende agricole. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato.

Lana, José Miguel (2003). Hacienda y gobierno del linaje en el nuevo orden de cosas: La gestión patrimonial de los marqueses de San Adrián durante el siglo xix. Revista de Historia Económica-Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, 21 (1), 79-112.

Lehmann, David (1984). Sharecropping and the Capitalist Transition in Agriculture: Some Evidence from the Highlands of Ecuador. Journal of Development Economics, 23 (2), 333-54.

Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio (MAIC) (various years). Bollettino di Statistiche Agrarie.

Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio (MAIC) (1863). Censimento Generale della Popolazione 1861. Firenze: Stamperia Reale.

Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio (MAIC) (1881). Notizie intorno alle condizioni dell’agricoltura negli anni 1878-1879. Firenze: Stamperia Reale.

Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio (MAIC) (1882). Censimento Generale della Popolazione 1881. Firenze: Tip. Fratelli Centenari.

Ministero di Agricoltura, Industria e Commercio (MAIC) (1891). I contratti agrari in Italia. Roma: Tip. Bertero.

Marshall, Alfred (1920). Principles of Political Economy. London: Macmillan and Co.

Martini, Angelo (1976). Manuale di metrologia: Ossia pesi e monete in uso attualmente e anticamente presso tutti i popoli. Roma: Era.

Merlini, Maria Chiara (2018). Una strada due canoniche: Alcune note per la storia di Certaldo in età medievale e moderna. Miscellanea Storica della Valdelsa, (335), 51-88.

Mill, John Stuart (1871). Principles of Political Economy. London: Longmans.

Mirri, Mario (1970). Mercato regionale e internazionale e mercato nazionale capitalistico come condizione dell’evoluzione interna della mezzadria in Toscana. In Agricoltura e sviluppo del capitalismo. Roma: Istituto Gramsci.

Mussari, Riccardo & Magliacani, Michela (2007). Agricultural Accounting in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries: The Case of the Noble Rucellai Family Farm in Campi. Accounting, Business & Financial History, 17 (1), 87-103.

Newbery, David M. (1975). The Choice of Rental Contract in Peasant Agriculture. In Lloyd Reynolds (Ed.), Agriculture in Development Theory (pp. 109-37). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Pazzagli, Carlo (1973). L’agricoltura toscana nella prima metà dell’Ottocento: Tecniche produttive e rapporti mezzadrili. Firenze: Olschki.

Pazzagli, Carlo (1979). Per la storia dell’agricoltura toscana nei secoli xix e xx: Dal Catasto particellare Lorenese al catasto agrario del 1929. Torino: Einaudi.

Pazzagli, R. (2008). Il sapere dell’agricoltura: Istruzione cultura, economia nell’Italia dell’Ottocento. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Pascual, Pere (2000). Els Torelló, una famılia igualadina d’advocats i propietaris. Barcelona: Rafael Dalmau.

Pérez Picazo, María Teresa (1991). Riqueza territorial y cambio agrícola en la Murcia del siglo xix: Aproximación al estudio de una contabilidad privada (circa 1800-19.2). Agricultura y sociedad, (61), 39-95.

Pescosolido. Guido (1998). Unità nazionale e sviluppo economico in Italia, 1750-1913. Roma/Bari: Laterza.

Planas, Jordi & Saguer, Enric (2005). Accounting Records of Large Rural Estates and the Dynamics of Agriculture in Catalonia (Spain), 1850-1950. Accounting, Business & Financial History, 15 (2), 171-85.

Poni, Carlo (1978). Azienda agraria e microstoria. Quaderni storici, 13 (39, 3), 801-05.

Reid, Joseph D. (1973). Sharecropping as an Understandable Market Response: The Post-Bellum South. The Journal of Economic History, 33 (1), 106-30.

Ridolfi, Cosimo (1858). Considerazioni sulla mezzeria toscana. Giornale Agrario Toscano.

Robertson, A. F. (1987). The Dynamics of Productive Relationships: African Share Contracts in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rogari, Sandro (1998). Rappresentanza Corporazione Conflitto: Ceti e figure dell’Italia rurale fra Otto e Novecento. Firenze: Centro Editoriale Toscano.

Rogari, Sandro (2002). Il problema della mezzadria toscana fra visione ideal tipica sonniniana e realtà fra ’800 e ’900. In Il suono della “lumaca”: I mezzadri del primo Novecento. Manduria: Piero Lacaita.

Rogari, Sandro (2009). Le campagne toscane nel ventennio postunitatio. Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, XLIX (1), 99-108.

Russo, Saverio (2013). La mezzadria nell’Italia meridionale. In Giuliana Biagioli & Rossano Pazzagli (Eds.), Mezzadri e mezzadrie tra Toscana e Mediterraneo: Una prospettiva storica (pp. 110-23). Pisa: Felici.

Sereni, Emilio (1947). Il capitalismo nelle campagne, 1860-1900. Torino: Einaudi.

Sereni, Emilio (2016). Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano. Roma/Bari: Laterza.

Simpson, James (2001). La crisis agraria de final de siglo xix: Una reconsideración. In Carles Sudrià & Daniel Tirado (Eds.), Peseta y protección: Comercio exterior, moneda y crecimiento económico en la España de la Restauración (pp. 99-118). Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona.

Serrano, José María, Sabaté, Marcela & Fillat, Carmen (2021). Trigo y política: El proteccionismo cerealista en el Parlamento, 1886-1890. Historia Agraria, (85), 157-84.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1974). Incentives and Risk Sharing in Sharecropping. Review of Economic Studies, (41), 219-55.

Tantini, Vincenzo (1852). Manuale teorico pratico della contabilità. Firenze: Vincenzo Tantini.

Zamagni, Vera (1981). Dalla periferia al centro: La seconda rinascita economica dell’Italia 1861-1981. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Winters, Donald L. (1978). Farmers without Farms: Agricultural Tenancy in Nineteenth Century Iowa. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Zanibelli, Giacomo (2019). La fattoria “La Canonica di Certaldo” (1858-1868): Uno studio storico-aziendale sull’agricoltura toscana nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento. In Giovanni Gregorini & Ezio Ritrovato (Eds.), Il settore agro-alimentare nella storia dell’economia europea (pp. 499-518). Milano: Franco Angeli.

Zanibelli, Giacomo (2022a). Il primo taking off: Alle origini della crescita agraria italiana: Una riflessione sugli anni Ottanta dell’Ottocento. Nuova Rivista Storica, CVI (2), 913-45.

Zanibelli, Giacomo (2022b). Mutamenti e sviluppo agrario nella Toscana meridionale dall’Ottocento preunitario al 1929: Uno studio strutturale sulla mezzadria attraverso un’analisi sulla produttività del grano. Rassegna Storica Toscana, LXVIII (2), 3-35.

Zuccagni-Orlandini, Attilio (1854). Ricerche statistiche sul Granducato di Toscana. Vol. 5. Firenze: Tip. Tofani.

↩︎ 1. The term is used in common language, though contracts usually did not refer to the word sharecropper .

↩︎ 2. Fattoria was the term used for for sharecropping farms in Tuscany.

↩︎ 3. The 1861 figure is not shown in the table because the regions are classified differently.

↩︎ 4. This term indicates the house that was provided by the landowner to the sharecropper. The production unit that formed the basis of the contract was the podere, which also included the land to be cultivated through the system of policoltura , and stables for livestock. The subsequent products were divided (1/2) between sharecropper and owner. The fattoria was the headquarters of the individual production units.

↩︎ 5. The values of the other provinces are reported: Livorno (34%), Pisa (47%), Pistoia (31%), Grosseto (27%), Lucca (19%) and Massa Carrara (12%).

↩︎ 6. In 1817 , the fattoria was acquired by the Conti family, with the death of the last heir (Princess Corsini - wife of Conti) was passed to the Counts Gherardi del Turco Piccolomini until the 1920s, when Rolando Barducci became owner. After Barducci’s death, the property passed to the San Marco Orphanage of Siena ( Merlini , 2018).

↩︎ 7. The map shows the land value per quadrato toscano . 1 quadrato toscano = 3,0416.19m 2 . The cartogram was built using the value of land cultivated with vines and olive trees, using data from the Catasto Leopoldino .

↩︎ 8. The average size of individual production units was 24 ha, the minimum value of 3 ha, the maximum of 65 and the standard deviation of 13 ha.

↩︎ 9. The idea of deepening a business structure located in the Certaldo area finds a precise connotation in the fact that already in the great period this territory had been carefully accessed within a specific social statistical study concerning the whole Grand Duchy of Tuscany, promoted by Attilio Zuccagni Orlandini (1854).

↩︎ 10. Zuccagni-Orlandini (1854: 184-85). The values reported by Zuccagni Orlandini are in quadrati toscani for the total surface and in staia for the forest agricultural area. In order to bring the values back to hectares, specific processing coefficients were used: 1 quadrato toscano = 3,406.19m 2 ; 1 staia = 1750.10m 2 .

↩︎ 11. The accounting and administrative documentation is kept at the State Archives of Siena. The size of the production units was in stiora , an ancient Tuscan unit of measure. This was converted into hectares through the following coefficient of transformation: 1 stiora =5.25 are.

↩︎ 12. Age corrections were made, taking 1870-74 as the reference period for the survey. For this reason, deaths and births dating as far back as 1858 have been considered. This made it possible to reconstitute the population of all the production units on the fattoria. (Table A1).

↩︎ 13. All males and females under the age of 10 have been included in the category of children.

↩︎ 14. The differences with the total value previously analysed are due to the fact that some fattorie could not rebuild the extension. The average number of sharecroppers per podere was 5, 1 for every 4 hectares. The total rent was 23,154 Lire and a per unit average of 182 Lire. The rent per hectare was 34 Lire.

↩︎ 15. Archivio di Stato di Siena (AS SI), Postunitario, Azienda la Canonica, Amministrazione. The production values, reported in ancient Tuscan units of measurement, were converted into those currently in use in agriculture. Subsequently, the value of production was estimated using Tuscan market prices and the agricultural deflator of the Bank of Italy. The conversions were made using the conversion coefficients contained in Martini (1976). The wheat an corn were brought back to the staia; wine and oil barili and fiaschi . The conversion coefficients for wine and oil are not the same, despite the names being so.

↩︎ 16. The analysis of commercial products (oil and wine) was carried out through the average values of production for regular time intervals.

↩︎ 17. For this reason, the trend has been calculated through a fixed based-index (1875-79 = 1) of the average production of some specific periods.

↩︎ 18. The analysis on the sales trend was carried out by calculating the percentage of the sales value on the total value of the landowner’s production (parte dominicale) of cereals and product sales for each year.

↩︎ 19. Taking the average price of some periods (1858-68 = 1), we can observe how between 1880 and 1886 these halved (0.5), only to rise again after the law of 1887 (0.7) went into effect .