1. INTRODUCTION

In every process of enclosure, there is a period of transition during which

enclosed land and open fields coexist as two parallel systems. In England, this

period lasted for several hundred years, from the 14th to well into the 19th

century. In Sweden, it was shorter. Although the privatisation of the commons

had already begun by the storskifte reform (1749-1827), it was not until the ordinances of enskifte (1803-27) and the subsequent laga skifte (1827-) that enclosures began to affect open fields. Roughly 60 years after the

initiation of these reforms, nearly all of the villages in the arable districts

of southern and western Sweden had been enclosed; a few decades later most

villages and hamlets in the eastern provinces also had passed through the

reform.

In a long-term perspective, this was indeed a rapid transition. Nevertheless,

from the perspective of the time, it stretched over a considerable period of

time. In many districts, the two systems existed side-by-side for two or even

three generations of farmers. In this article, the situation in an area on the

central plains of the province of Västergötland, in western Sweden, will be examined more closely. Prior to enclosure, the

area was dominated by large villages with extensive open fields, covering

almost all of the land. The first enclosure in the area was initiated shortly

after the adoption of the enskifte legislation for this province in 1804. It was, however, not until the 1860s that

the last villages entered the process of enclosure. During this period of

transition, the plains could be described as a mosaic of enclosed and

open-field land where systems of farming differed from one neighbouring village

to another. This situation leads to several observations.

First, the parallel existence of enclosed and open-field land systems actually

makes it possible for us as historians to compare the two regimes. In this

study, the plains area in Västergötland, where conditions (for example, soil, climate, market possibilities, and

farming traditions) differed very little from one village to another, will be

used as a “historical laboratory” of enclosure and open-field systems. Seeds, livestock, aspects of farming

technology, and land prices will be measured in order to isolate the effects of

enclosure on agrarian development.

A second and equally central point is that contemporary farmers could

realistically have made a similar comparison to the one in this study. Since

enclosed and open-field villages lay side-by-side on the plains for so many

years, the consequences of the reform were obvious for everyone, given that

peasants from both property regimes met at church on Sundays or as relatives

and friends. Farmers must thus have been fully able to assess the advantages

and disadvantages of the two systems, as well as judge which of the two systems

suited them best.

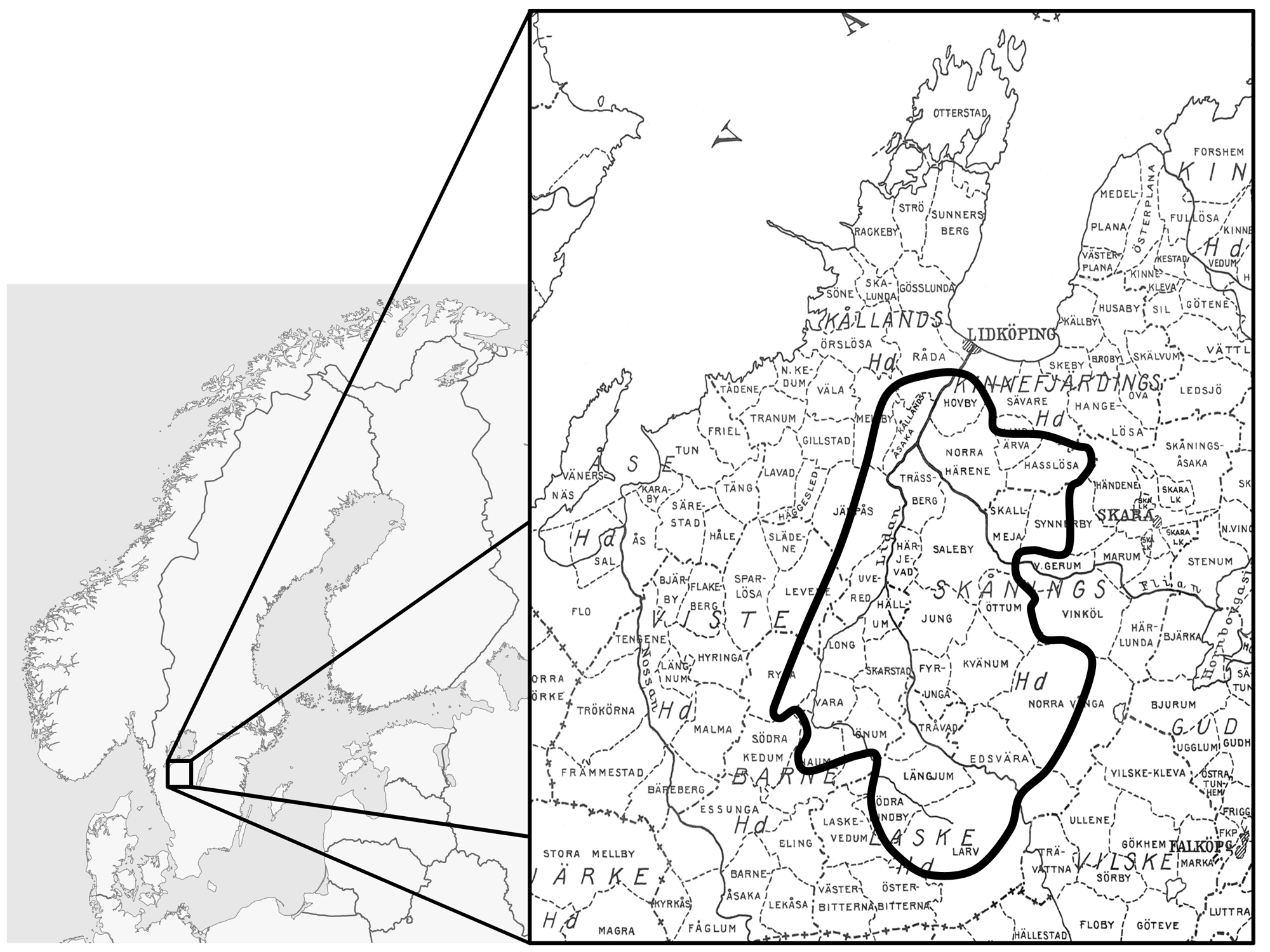

Map 1

The area of research

This latter situation gives rise to third and final point, namely that the

parallel existence of these two agricultural systems requires an explanation in

itself. In a perfect situation in which farmers and landowners had access to

reliable information about the systems and were able to make a rational choice,

the most efficient one would soon prevail. Arguably, farmers were reasonably

well-informed. The foundation of this investigation must also rest on the idea

that they acted rationally. If enclosures were the best option, as claimed both

by the experts of that time and by most later agrarian historians, landowners

would rapidly opt for this solution. Why, then, did the situation of parallel

existence last for so long?

2. The reversed institutional and social setting

One objection to the argument above is as follows: the parties involved might

indeed have been rational, but they might not have been able to choose a course

of action freely. In the real world, their decisions were bound by

institutional, political and cultural constraints, and they also had to

consider the costs of the reform. Furthermore, one group might have considered

enclosure to be rational (for example, the great landowners), but not others

(for example, the landless population). From this perspective, the systems’ concurrent existence could be explained as the result of institutional

imperfections (using an institutional approach) or of an on-going class

struggle (employing a materialistic approach). In both cases, the situation in

England can provide illustrative examples1.

The debate about conflicting interests in the British enclosure process

comprises one of the main threads of social history. According to Robert Allen’s (1982, 1992) investigations into enclosures in the Midlands in the 18th and 19th centuries, these reforms mainly resulted in a redistribution of agrarian

incomes, and not so much of an increase in agrarian production2. Others would disagree, but few would claim that commoners and copyholders

favoured the reform. Regardless of whether enclosure was a plain enough case of class robbery or not, there is well-documented resistance towards the reform, an element that

can provide at least part of an explanation to the long period of

open-field-enclosure coexistence3.

At the same time, formal institutions hindered a rapid transition. Before the

introduction of parliamentary enclosure in the 18th century, unanimity among landowners was required in order to enclose open

fields. Among others, McCloskey (1975: 127-33) pointed out how this stipulation

made enclosures extremely complicated; often bribes or threats often seem to

have been necessitated in order to deal with reluctant stakeholders4. For parliamentary enclosures, the support required was reduced to owners

representing 75% or 80% of the land. Even in this situation, however, the

process was difficult and expensive5. The fact that landowners were willing to endure these high costs of transition

most likely reflects a situation in which considerably higher returns from the

land could be expected in the enclosed regime. With easier and cheaper legal

procedures, these gains would have been even higher and, as Turner (1980:

169-70) suggested, enclosures would most likely also have been initiated

earlier. Thus, it appears the English institutional situation enabled the

open-field system to survive longer than was economically desirable (at least

from a large-landowner perspective).

The Swedish case makes an interesting contrast. The enskifte legislation (1803-27) gave every landowner the right to individual enclosure,

that is, the removal of his share of the open fields into one single piece of

land6. In several ways, it also advocated general enclosures: the enclosure of the

whole village.

In Laga skifte (1827-), this institutional situation was taken one step further to absolute priority of enclosure: If one single landowner wanted to enclose his property, the whole village had

to be enclosed, regardless of the opinion of the other stakeholders. Compared

to pre-parliamentary enclosure in England, a reversed institutional situation

was established in Sweden: unanimity among landowners was in fact required in

order to maintain the open fields.

At the same time, the social setting in the two countries differed. In many

respects, Sweden represents Robert Allen’s (1992: 303-11) lost yeoman alternative in English agrarian history. Through several reforms, the peasantry was

strengthened and advanced economically and politically throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. While in England, land passed from the peasantry to the gentry, in

Sweden, the state and nobility sold off much of their land to the peasants7.

Taking all of these developments into consideration, there has been a strong

tendency in recent Swedish historiography to weave the advancement of the

peasantry and advancement of enclosures into one single story of success8. As peasants are seen as rational and successful, and enclosures are also

understood as rational and successful, it has been natural to associate the

latter with the former. In contrast to an older tradition of research where

agrarian modernisation (often under the influence of the English case) was seen

as a “top-down” process driven by enlightened gentlemen-farmers and the state more or less

against the will of the peasantry9, agrarian revolution and enclosures are now to an increasing degree understood

as a “bottom-up” process driven by an advancing peasantry. One recurrent argument in this

context is that free-holders actually initiated most of the enclosures.

From the perspective of this study, however, it is more remarkable that it took

so long before free-holders actually did pursue enclosure. In most Swedish

villages, there were only free-holders and, consequently, only free-holders

could start the reform. Given the situation in which every landowner since the

early 19th century had the right to enclose his land, why did it take 40 to 50 years

before the great wave of reform swept across the country10? In other words, if free-holders acted rationally, if –as is generally assumed– enclosure meant a great advance, how could open fields survive for so long in a

situation in which every landowner had a veto against their continued

existence?

3. Area of research

In the following sections, results from a study on enclosure and open-field

farming on the central plains of Västergötland will be presented. From a historiographical point of view, this is classic

ground in Swedish research. It was the main area of study in Carl-Johan Gadds’ (1983) Järn och potatis, (“Iron and potatoes”), considered by many to be the most important Swedish in-depth study of the

agricultural revolution. In his analysis, farming technology, crop rotations,

and social and demographical developments were carefully investigated.

Enclosures were also discussed, but mainly on a hypothetical level. In fact,

Gadd did not empirically examine enclosures on the Västergötland plains.

Yet if we want to contrast the two systems, it is hard to find any better area

to research. Before enclosure, virtually all land was used as open fields. As

grazing was integrated between the villages, these fields sometimes stretched

for many miles. The large-scale character of the agrarian landscape was further

strengthened by the sizeable villages that in some cases consisted of up to 80

individual farmsteads. In such an area, enclosures meant a total remodelling of

the whole agrarian landscape. The fact that the villages were so large is also

interesting from an institutional point of view. With so many stakeholders, the

absolute priority of enclosure was really put to the test.

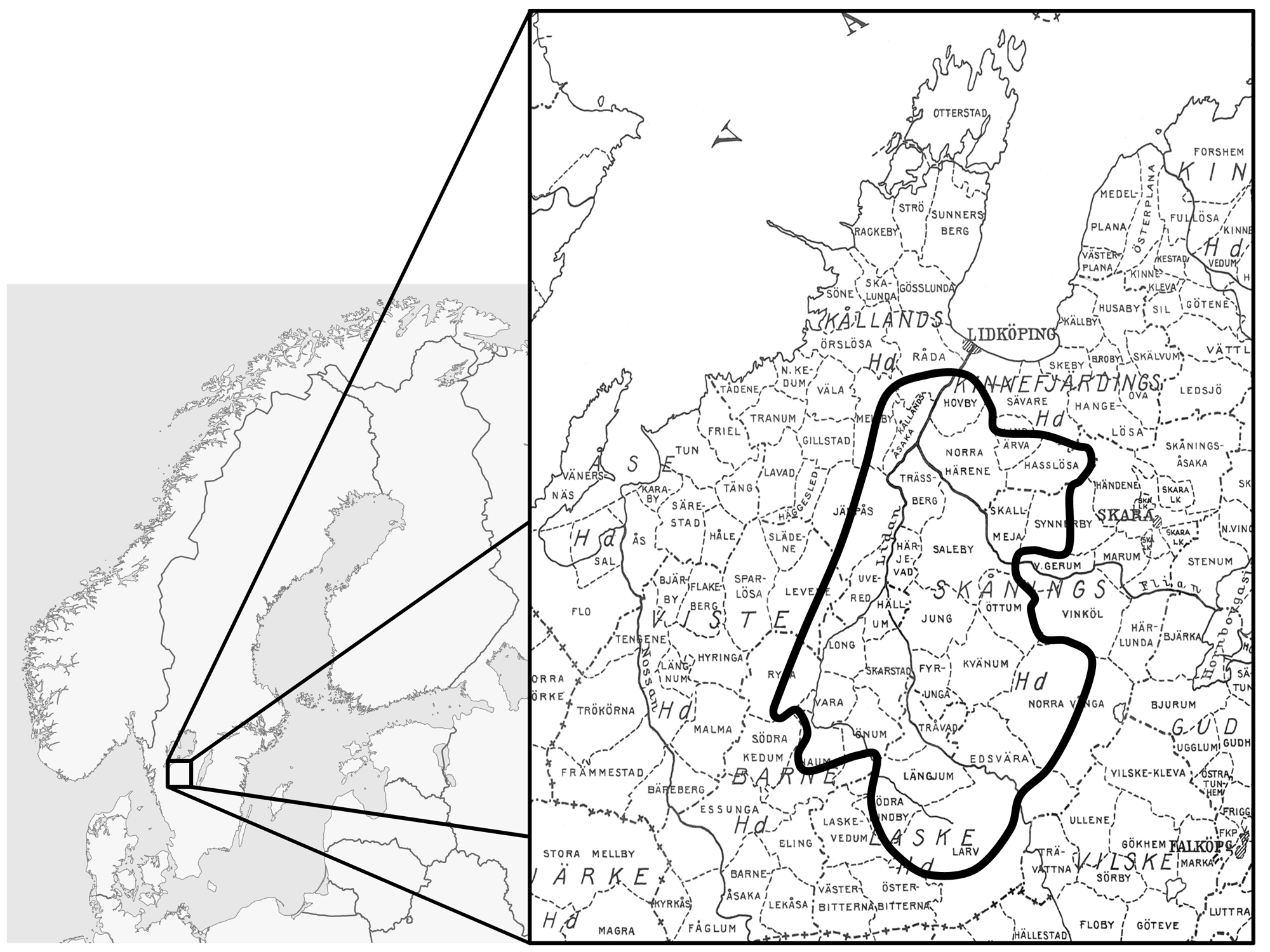

Map 2

Territorial organisation prior to enclosure according to late 18th century storskifte maps

The distance from north to the south on the map is 36 kilometres.

Sources: the map is compiled from the storskifte reform maps of 85 individual villages. A few older and newer cadastral maps have also been consulted. At a limited number of spots the territorial organisation has been deduced from settlement structure combined with field patterns in surrounding areas. White areas lack sufficient data.

Traditional farming on the plains was based on a two-field system (see maps 2

and 4)11. Every year, half of the land was used for crops or meadows. The other half lay

fallow and was used as common pasture. The farmsteads were clustered along the

wooden fence that separated the two halves. One year, cattle were let out to

graze on one side of the fence, and the next year on the other. The fact that

there were only two fields, that there was no separately fenced waste, and also

that grazing was co-ordinated between the villages, reduced the need for fences

to a minimum. This was important since the area virtually lacked all recourse

to wood.

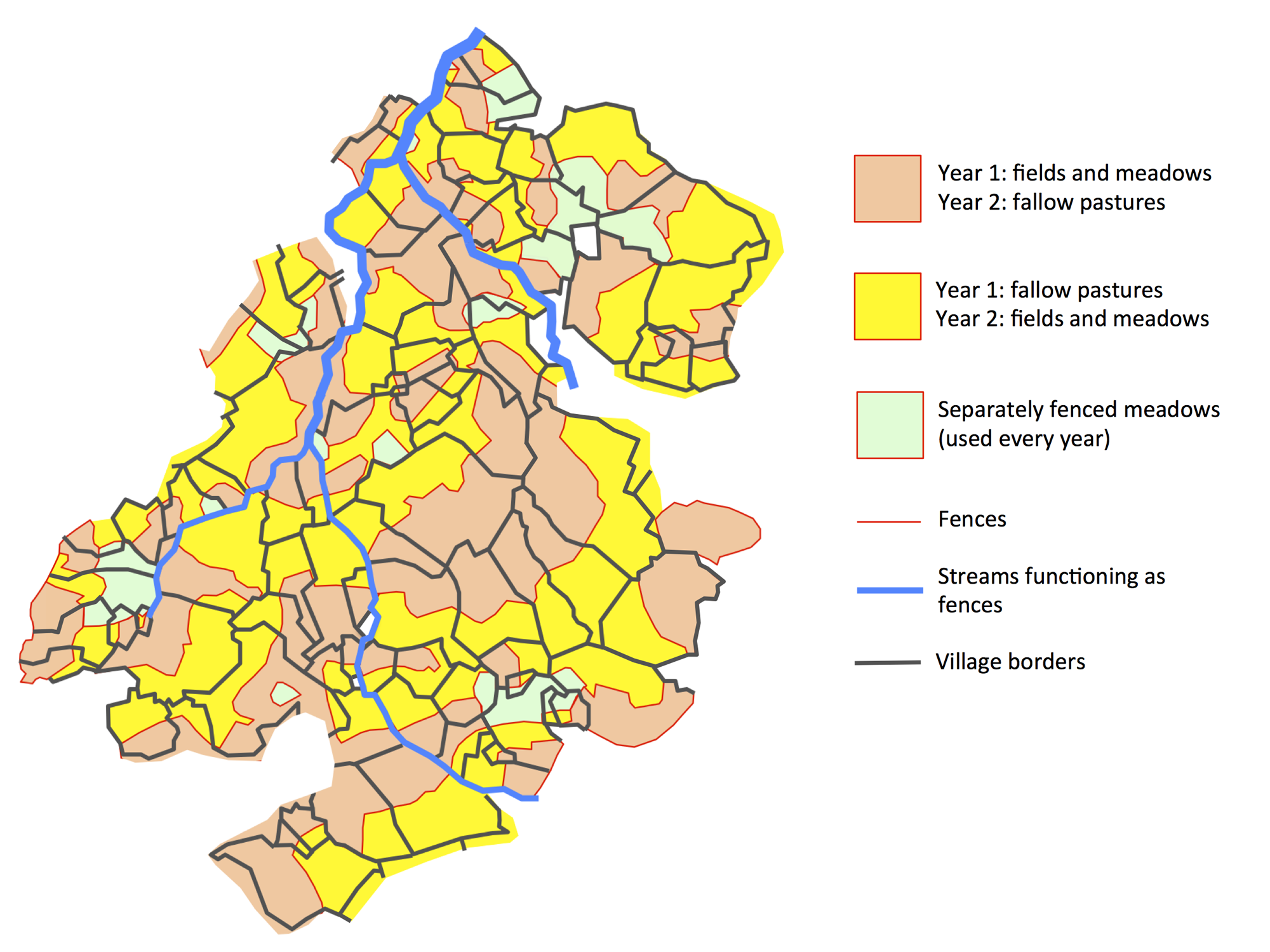

Map 3

Geographical chronology of enclosures (enskifte or laga skifte)

Sources: enskifte and laga skifte reform acts.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, this farming regime was a significant site for animal production, but

gradually, as the population grew, grain became the main specialisation. By the

1780s, exports of cereals was mentioned as the only way for local farmers to

get access to markets. Surplus production was largely sold to the ironmaking

regions of Bergslagen and Värmland on the other side of Lake Vänern. Cows, pigs, and sheep were kept for local needs. However, their numbers

declined steadily over time.

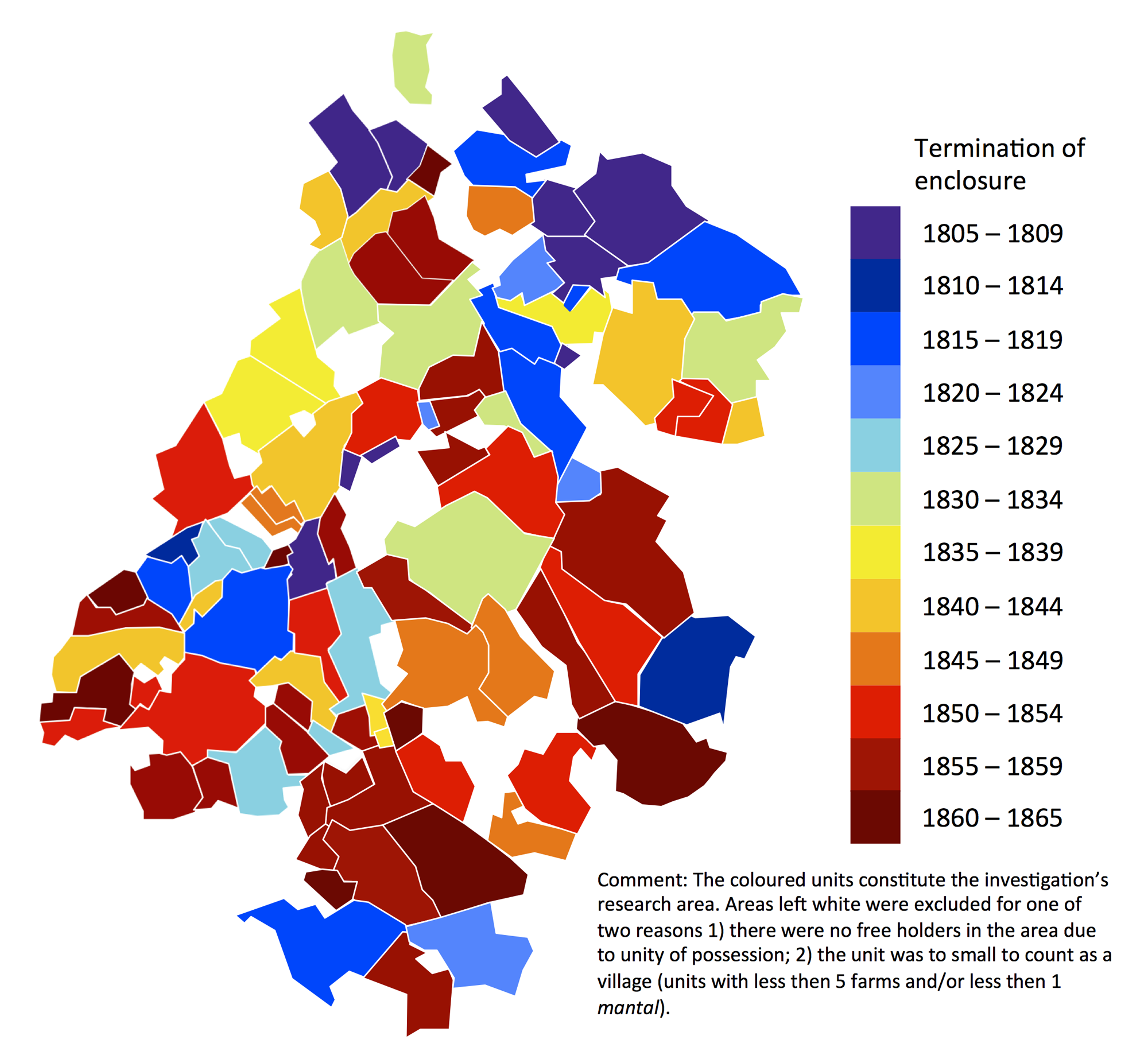

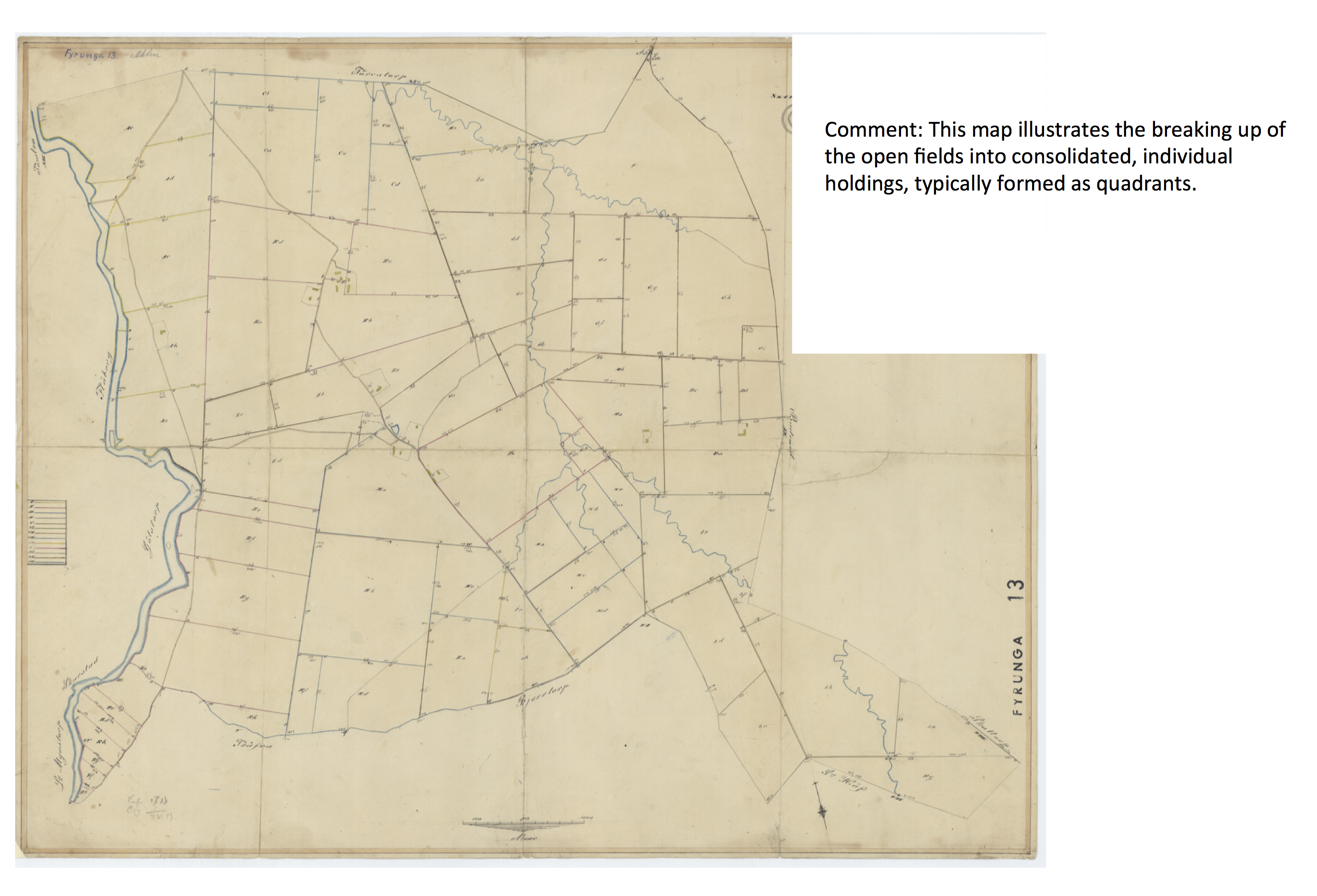

Map 4

Storskifte map of Fyrunga in 1785

Source: Digital archive of Lantmäteristyrelsen.

One crucial problem in this context was the growing shortage of fodder. As more

and more land was reclaimed during the 18th and 19th centuries, the area covered with meadows was correspondingly reduced. With

fewer meadows, it became harder to feed the cattle during the winter; and if

the number of cattle was reduced, there were fewer sources of traction power

and manure for the fields –a classic dilemma of traditional farming. The management of this situation

constitutes a main thread in Carl Johan Gadd’s research into the region. In contrast, the scattering of land –often identified as one of the drawbacks of the open-field system– seems to have been less of a problem. During the Storskifte land reform in the late 18th century, the number of strips belonging to each farm was substantially reduced;

in many cases, to just three or four (see Map 4). However, as villages were

large, farmers often had to walk considerable distances to reach their land.

Map 5

Laga skifte of Fyrunga village in 1847

Source: enclosure act 16-FYR-13, digital archive of Lantmäterimyndigheten.

The first enclosure in this study’s area of research took place in Åsaka in 1805. Figure 1 and Map 3 offers an overview of the chronology of the

subsequent acts of enskifte and laga skifte.The figure is based on the time when each enclosure was initiated, the map

depicts its conclusion. As seen in the figure, the early 1850s can be

identified as the most intensive period in terms of new applications. At this

phase, almost half a century had passed since the introduction of enskifte reform in 1804, though it also must be noted that the more radical laga skifte ordinance in 1827 was more recent. Legal enclosure processes often stretched

over several years, sometime more than a decade. It was not until the

termination of enclosure in Längjum in 1865 that the process in the area was finally concluded.

Figure 1

The chronology of enclosure in the research area:

number of mantal entering the process per year

Note: village units of ≥1 mantal and ≥ 5 farmsteads (in the case of individual enskiften smaller units part of large enough villages are also included).

Sources: cadastral act registers; enclosure acts (accessible via the Swedish

Authority of Land Surveying,

).

4. Methodological considerations

The following analysis is based on probate inventories from free-holders on

enclosed and open-field land, records of land transactions, and enclosure acts

from 88 villages. The probate inventories list tools, animals, and seeds, which

enable us to reconstruct agricultural practices within the two systems in some

detail. Records of land sales are used to reconstruct market prices of enclosed

and open-field land, which reflects both its production potential and buyers’ interpretation of the two systems. Enclosure acts make it possible to establish

the time of enclosure for each farm being observed.

In order to be able to take the size of the farmsteads into account, quantities

of land are measured in mantal units. These comprised the official Swedish measurement of land during the

period of investigation and were used primarily for taxation purposes as well

as in some situations during enclosure. The unit of 0.25 mantal used in the present investigation equals the median size of a farmstead

throughout the period studied. On average a 0.25 mantal farm encompassed over 28 hectares of land12.

The mantal appears in most documents regarding farms, and has also the strategic advantage

of being stable over time. If, for example, a farm of 0.25 mantal was divided into two separate farmsteads of equal size, the result was two

units of 0.125 mantal each. The fact that the total mantal of specific areas remained unchanged throughout the period in question enables

us to calculate changes in production and land prices over time. At the same

time, however, it must also be stressed that it is a rather rough measurement.

The “real size” of the mantal, as measured in for example land value or seeds, could vary considerably. This

disparity is also reflected in a high level of statistical variation in the

material used in the investigation13. Consequently, an ample number of observations are required in order to make

results statistically reliable. Crosschecks have been done on the collected

data, using observations preceding or at the very beginning of the process of

enclosure, to ensure that early-enclosed land was not, on average, in the

possession of more/less resources per mantal than land enclosed later. No such tendency could be discerned14.

In total, the study is based on evidence from 2,041 records of land sales from

1804-62 and 1,342 probate inventories from 1795-1869. The most reliable results

are from the period from the early 1830s to the late 1840s when there are

plenty of both enclosed and open-field land observations. Regarding early

enclosed and late open-field land there are fewer sources. Still, with only one

exception, no cohorts with less than 20 observations are used in the

investigation. All differences between enclosed and open-field land discussed

in the text are statistically significant at the 0.05 level unless otherwise

stated.15

5. Land prices

The prices of enclosed and open-field land are useful as indicators of the

development within the two systems16. To a certain extent, market prices of these types of land should reflect the

effectiveness of each system. If agricultural productivity rose as a result of

enclosures, then the price of enclosed land should rise as well.

At the same time, however, other factors must be taken into account, such as

expectations of future returns from the land. If considerable gains could be expected from enclosure, this

might also affect prices on unenclosed land. Another aspect of potential

importance is the reform’s impact on agricultural capital. In practice, an enclosure led to the

substantial destruction of capital in the form of buildings and fences, a

capital that had to be reconstructed. Therefore, at least during a transition

period, enclosed land might actually have been traded at lower prices than

unenclosed land, even if its production potentials were better.

In a long-term perspective, other possible scenarios also emerge. If farmers

began to regard enclosure as inevitable, it is conceivable that existing

capital that was bound up in the old village structure actually began to be

regarded as worthless –a kind of “sunk capital”. Therefore, it can be imagined that unenclosed land was traded at a lower price

–even in a situation in which actual productivity was similar. Thus, on the basis

of a price index for enclosed and open-field land, the peasants’ understanding of the two systems may also be discussed.

Figure 2 presents the overall price development for land for the period studied.

It is notable how the price of land started to rise precisely in the period of

the most intensive enclosures in the 1840s and early 1850s. In the following

decade (which also was the time of the Crimean war and the start of massive

exports of oats from Western Sweden to England), they exploded.

What was the role of enclosure in this development? In Figure 3, the average

prices for open-field and enclosed land from 1818-53 are presented.

In the beginning of the period studied, enclosed land was not more attractive on

the property market than open-field land; instead, the tendency is the

opposite. This pattern, however, rapidly changes from the mid-1830s. For the

rest of the period of study, enclosed land was traded at substantially higher

prices than open-field land.

Figure 2

Overall price (arithmetic mean) development for unprivileged land in the

research area, 1804-62. Riksdaler riksgäld per ¼ mantal (median farm size)

Note: transactions of ≥ 1/24 < 1 mantal.

Sources: register of land sales (uppbudslängder) in Skåning, Barne, Kålland, Kinnefjärding and Laske hundreds. Regional Archives of Gothenburg (Riksarkivet i Göteborg).

Figure 3

Average prices (arithmetic mean) of enclosed and open-field land in the research

area, 1818-53. Riksdaler riksgäld per ¼ mantal of unprivileged land

Notes: transactions of ≥1/24 <1 mantal skatte- and kronoskatte land. Exclusions include: transactions where the size in mantal could not be established; land under the process of enclosure (defined here as

from its initiation until three years after its legal termination);

transactions involving benefits in kind to the former owners (undantag) or the covering of their debts. The differences between the two categories of

land from 1826-31, 1834-39/1844-49 and 1848-53 are statistically significant at

the 0.05 level.

Sources: see Figure 2.

The previous discussion points to one possible explanation for the low prices

paid for enclosed land during the early period of study, namely that part of

the old “open-field bound” farm capital, which was eliminated by enclosure, had not yet been fully

displaced by new inversions. One important factor in this context was probably

that the 1820s were a difficult period for European farmers. The blissful years

of the Napoleonic wars were over, and both grain prices and land prices went

down. This economic shift made investments more risky and capital more

difficult to access. It is reasonable to assume that this development affected

newly enclosed land, which urgently required large investments, particularly

hard.

The fact that enclosed land during this period was traded at a reduced price

offers at least part of an explanation for the “parallel existence” and slow advance of the enclosed regime. It is hardly surprising that most

farmers chose not to opt for enclosure if the expected outcomes of such a

project did not include an increase in the value of the farm. If enclosures

were to be economically justified, prices on enclosed land needed to be higher than on open-field land. Similarly, it is also logical that considerably more

enclosures occurred during the later phase of the study, when enclosed land had

been up-valued by the market and was traded at substantially higher prices than

open-field land.

An important question in this context is what caused this growing divergence.

One possibility is, of course, that this shift reflected developments on the

ground. In this scenario, the enclosed system now effectively outcompeted the

open-field regime in terms of efficiency and land productivity. In accordance

with the previous discussion, however, there is also another possibility,

namely that that the difference in market prices was the result of

psychological mechanisms and assessments about the future. By the early 1840s,

there must have been a growing awareness that the open-field system was coming

to an end, especially considering the absolute priority of enclosure and the

successive breaking down of the system in village after village. If farmers

began to regard enclosure as inevitable, it is conceivable that existing

capital that was bound up in the old village structure (fences, buildings and

so on) actually began to be regarded as worthless –a kind of “sunk capital” that no one was willing to pay for at the market. Hypothetically, therefore, it

can be assumed that unenclosed land was traded at a lower price even in

situations in which its underlying productivity was still comparable to that of

enclosed land.

Thus, in order to identify which of these two scenarios best resembles the

actual development, it is necessary to study the productivity of the two land

regimes.

6. Seeds, land reclamations, and cropping systems

The main source of the following analysis consists of probate inventories from

deceased freeholders in the research area from 1795-186917. Of the 1,342 inventories used in the investigation, 1,081 provide information

on seeds as part of farm capital. This fact enables us to measure grain

cultivation within the two property regimes. In Figure 4, the seeds of grain,

peas, and potatoes are measured in weighted barrels, using the methodology of

Carl-Johan Gadd. Approximately one weighed barrel equals a net sown area of 0.5

hectare.

Figure 4

Seeds on enclosed and open-field land in the research area, 1809-68.

Weighted barrels per ¼ mantal (arithmetic mean)

Notes: 1 Swedish barrel of wheat = 1.33 weighted barrel; rye, 1; barley, 1;

mixed barley-oats, 0.67; oats, 0.5; peas, 1.33; potatoes, 0.33 (after Gadd,

1983: 90). 1 Swedish barrel = 156 litres. Observations from the year of the

implementation of enclosures and the following three years have been excluded.

The differences between the two categories of land during the period from

1849-60 are statistically significant at the 0.05 level if this period is not

divided into shorter segments of time.

Sources: probate inventories from the häradsrätt local courts. (digital versions at

; originals at Riksarkivet in Gothenburg); records of taxation and real estate (mantals och fastighetstaxeringslängder, Riksarkivet, Gothenburg); cadastral act registers; enclosure acts (

).

Figure 5

Seeds from different crops on enclosed and open-field land in the research area,

1795-1869. Weighted barrels per ¼ mantal (arithmetic mean)

Sources and notes: see Figure 4. The differences between the two categories of

land are statistically significant at the 0.05 level regarding wheat (all

studied intervals) and rye (1820-34 and 1835-44).

According to Gadd’s (1983: 223-24) interpretation, enclosures were one of the main driving forces

behind land reclamations on the plains. Enclosures did not only incentivise

farmers to convert more of their property into arable land. In fact, the reform

actually forced them to do so, as the new land belonging to many farmsteads was

comprised of meadows originally located on the outskirts of the old villages.

This argument seems plausible and is commonplace in literature on the agrarian

revolution in Sweden. It has, however, never been empirically tested. The

results depicted in Figure 4 contradict this theory, as the amount of seeds

remained almost identical over a long period of time in both property regimes.

This observation implies that land reclamation was actually not greater on enclosed land. Not until the 1850s (when practically all land had

already entered into the process of enclosure) can we observe a change in this

respect. The amount of seeds on enclosed land then escalated, creating a gap

between this land and the small remaining portions of open-field land.

In Figure 5, seeds from the individual crops are presented. These results enable

a more detailed analysis of farming within the two systems.

Also with regards to crops, the seeds used on enclosed and open-field land long

remained more or less the same. Presumably, this pattern would imply that

crop-rotations were also similar.

According to contemporary agrarian reformers, one of the main advantages of

enclosure was that it facilitated the transition to convertible husbandry18. In this way, fodder crops such as clover could be integrated into crop

rotations, providing a solution to the old land-reclamation/fodder shortage

dilemma.

Lamentably, there is no information about clover seeds in the probate

inventories. The potential shift from a two-field system to convertible

husbandry can, however, also be studied by looking at the cultivation of other

crops. The old two-field system practiced on the plains was first and foremost

a system of spring grain (barley, oats and mixed oats-barley) cultivation.

Winter grain (wheat and rye) was difficult to cultivate since the best time for

sowing was in August and would have interfered with common grazing on fallow

fields. If temporary fences were not used, farmers would have had to wait to

sow their rye until well into September, when the animals were moved from the

fallow fields to the stubble on the harvested fields. This practice was risky

since it shortened the growing season. As winter grains produced better yields

than barley and oats and, as cash crops, were also more valuable, the

difficulty in cultivating these crops was one of the main disadvantages of the

old order. For similar reasons, potatoes and peas were also difficult to

integrate into the two-field system and required temporary fences. If enclosed

land farmers had abandoned the old system, we would expect a significant

increase in the cultivation of these crops.

As can be seen in Figure 5, farmers on enclosed land did indeed cultivate more

rye and wheat than farmers on open-field land. However, the difference was by

no means conclusive and does not indicate a general shift towards convertible

husbandry. It was not until the late 1850s and 1860s that there was a

distinctive change in this respect, with an increase in rye, wheat, potatoes

and peas and the introduction of vetch as a fodder crop. In addition, the

cultivation of oats grew as British market demand exploded, while barley and

mixed oats-barley fell behind. This shift occurred simultaneously with the

massive increase in the amount of seeds discussed earlier. It does not require

much imagination to identify this period as the time of the decisive

breakthrough of convertible husbandry on the plain. This result is supported

both by Carl-Johan Gadd’s interpretation and contemporary reports from the area19.

Ultimately, enclosure seems to have had little immediate effect on cereal production on the plains. The major changes did not occur until

towards the very end of the period of parallel existence, 45-50 years after the

initiation of reform. Up until then, farming within the two regimes was very

similar. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that the size of the yields is

unknown. Was it greater on enclosed land? Due to the lack of contemporary data

from the farm or village level, the question will be addressed indirectly,

through an analysis of livestock possession.

7. The livestock

Livestock was, in several ways, the hub of the farming economy. Oxen and horses

provided traction power that enabled the households to farm the land. The horse

was used for transport and was also important as a status symbol. All animals

provided the manure needed to maintain the fertility of the land. Given the

situation described above (in which acreage under tillage remained almost

identical for both enclosed and open-field land until the early 1850s) the

possession of livestock is therefore an important indicator of the underlying

productivity within the two systems. It reflects how much fodder the farms

could produce. It indicates how much manure there was to fertilise the fields

and, indirectly, probably also how large the yields were. In Figure 6, the

number of horses, oxen, and cows within the two systems is presented.

Similar to the case of the seeds, there is an increase in livestock on enclosed

land towards the end of the period. Until the early 1850s, however,

enclosed-land farmers were not better equipped with livestock than farmers with

open-field land.

A closer look reveals some differences between the two systems. Farmers with

enclosed land tended to own slightly more horses than farmers with open fields.

The latter, in their turn, possessed more oxen. Horses were, in several ways,

the “up-market” alternative; they worked faster, demanded more fodder, were more expensive, and

offered more prestige to the owner. Oxen provided more traction power per unit

of fodder but were slow and of insignificant symbolic value. Consequently, the

fact that enclosed-land farmers owned more horses would suggest a slight

advantage for this property regime in terms of economic performance. It must,

however, be noted that the only differences that are statistically significant

at the 0.05 level are those regarding oxen.

Figure 6

Possession of horses, oxen and cows on enclosed and open-field land in the

research area, 1795-1869. Number of animals per ¼ mantal (arithmetic mean)

Notes: 1 bullock is counted as 0.5 oxen. The differences in possession of oxen

1820-34 and 1845-54 are statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

Sources: see Figure 4.

Thus far, the numbers of animals have been discussed. What has not yet been taken into account is the

quality of the livestock. Better-fed animals weighed more, were stronger, and

produced more manure. They were also traded at higher prices on the market.

Figure 7 compares the values of horses and cows (the two animals found on every

farm) in probate inventories from the two categories of land. In Figure 8, the total value of all animals on the two types of farms is presented.

Figure 7

Average value of horses (above) and cows (below) in the research area, 1820-61. Riksdaler riksgäld per animal (arithmetic mean)

Sources: see Figure 4.

The most important tendency shown in the figure is that animal values for both categories of land rose sharply from the late 1830s and onwards. Inflation

explains part of this development; the consumer price index rose 30% in 1840-60

(Edvinsson & Söderberg, 2011). The rising values of the livestock must, however also reflect an

increase in their size and quality, which reasonably also suggests that they

were better fed. As this development started before convertible husbandry and

clover cultivation had begun in earnest, the most probable source of new fuel

for the animals was an increased use of oats as fodder. This improvement in

feed could be achieved just as easily in an open-field system as on enclosed

land.

Not until the very last years of the investigation, when there were only small

portions of open-field land left on the plains, can we distinguish a difference

between the two regimes. In this period, enclosed land seems to gain an

advantage in terms of the total value of the livestock. Even if the difference

is not statistically significant, it certainly makes sense in the light of the

previous result of the study. The fact that farmers with enclosed land adopted

convertible husbandry from the 1850s must have improved the fodder situation

within this system. At the same time, more draught animals were required on

enclosed land as grain cultivation rapidly expanded.

Figure 8

Total value of the livestock on enclosed and open-field land in the research

area, 1820-61. Riksdaler riksgäld per 0.25 mantal (arithmetic mean)

Note: the differences after ca. 1850 are not statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

>Sources: see Figure 4.

8. The spread of innovation: the iron plough

The final section of the empirical study involves an analysis of the

introduction of the iron plough. According Carl-Johan Gadd (1983: 153-60,

259-62) this adoption was one of the most important agricultural innovations on

the plains, reducing the animal power needed to work the land. Figure 9

presents the breakthrough of the innovation. In order to be able to follow the

process from the beginning, the plough’s early development on enclosed land has been included in the figure, even if it

is based on a very limited number of observations.

The scarce empirical evidence from enclosed land from the 1810s indicates that

the introduction of the iron plough began earlier on this category of land.

This phenomenon was probably due to the fact that several early enclosed

villages were situated very close to what, from Gadd’s (1983: 157, 159) results, can be identified as the epicentre of the spread of

the new invention: the peninsula of Kålland, a few miles northwest of the research area. All early enclosed-land

ploughs are from villages close to this area.

Figure 9

The spread of the iron plough on enclosed and open-field land in the research

area, 1811-43. Percentage of farms with the best plough in iron

Notes: if the designation is unclear, the type of plough has been determined

from the value of the plough (iron ploughs were considerably more expensive

than other ploughs) according to Gadd’s (1983: 153-56) methodology. The differences between enclosed and open-field

land after ca. 1820 are not statistically significant at the 0.05 level. The earliest cohort for enclosed land is based on only 5 observations.

Sources: see Figure 4.

Once iron ploughs had started to take off, their use appears to have advanced

somewhat faster on open-field land. The fact that farmers lived close together

in villages and could study the use of the new plough when neighbours worked

the land on the adjacent strips might have accelerated the spread of innovation

within the open-field regime. It must nonetheless be stressed that the

differences between the two categories of land are small and by no means

statistically significant.

9. The re-emergence of the old order within the new regime

Thus far, it can be concluded that, over a long period of time, there were

striking similarities between the two property systems. In spite of the massive

reorganisation of the agricultural and institutional landscape, farmers with

enclosed land did not reclaim more land, sow more seeds, or possess more

animals than farmers with open-field land. Neither did they adopt innovations

such as the iron plough more rapidly. Most strategic in this context is the

fact that farmers with enclosed land also continued to employ the traditional

two-field system up until the 1850s, when convertible husbandry was finally

adopted. It was not until then, in the very last phase of the “parallel existence”, that the system of enclosed land secured a clear advantage over the

open-fields. Why did the dynamic effects of the reform not come earlier? Why

did the farmers with enclosed land not adopt convertible husbandry right from

the start?

According to observers of the time, there were several problems attached to the

adoption of modern cropping systems on the plains. In the old order, half the

fields were put aside as fallow every year. This system might seem like a big

waste of land, but was a result of the fact that the fallow was necessary for

working and preparing the stiff and heavy clay soils, both mechanically and

with the help of the winter frost. Within convertible husbandry, fallow land

was drastically reduced. Most of the ploughing now had to be performed during

the busy spring season, which could create insurmountable demands on both

draught animals and human labour. In addition, convertible husbandry required

heavy complementary investments if its potential was to be exploited properly –not least the draining of the wet, clayey soils20.

Another problem connected to the change in farming system concerns the issue of

fences. As has been stated above, farmers in the area did not have their own

wood resources; everything had to be imported. The central foundations of the

old agricultural regime (the two-field system, the large villages, and the

enormous grazing communities that covered the open fields of several villages)

were all aimed at reducing these costs as much as possible. The fundamental

idea behind enclosure provided the opposite approach: each farm should be

fenced separately. In practice, this would indicate that the total length of

the fences was multiplied. If convertible husbandry was to be adopted in

addition to enclosure, the length of the fences would have to be multiplied

once more. The two-field system had, as is apparent by its name, two fields;

convertible husbandry with crop rotation in this region typically had eight.

For contemporary farmers, the use of eight separately fenced fields was simply

not an option. Thus, they continued to use the old two-field system in the

enclosed regime21. Furthermore, as landowners farmed their land in a similar manner side-by-side,

it was in fact also possible to integrate fences between neighbours and leave

the fields open to allow grazing over the boundaries between the farms. These

kinds of systems can be discerned on a number of cadastral maps of farms from

the area22. Thus, not only the two-field system was re-established in the enclosed regime,

but also, to some extent, the open fields!

One important factor in this context is that many enskifte and early laga skifte enclosures in this region were actually implemented in a way that facilitated

this sort of cooperation over fences. Even if the pronounced idea behind the

reform was that each farm unit should be separated from its neighbours; in

practice larger units of partition were commonly used. Thus, if the landowners

within the same “land register unit” (jordeboksenhet) agreed, up until about 1840, they were, in general, permitted to secure their

share of the village in one common allotment23. Typically this type of unit consisted of 0.5-1 mantal and harboured two to five individual farmsteads. If these farms were treated as

one unit during enclosures, the costs of the reform could be kept down, an

ambition that is sometimes explicitly expressed in the enclosure proceedings24. The concerned parties were then left to decide how to divide up their new land

within each land-register unit. From later records of land surveillance, we

know that they often chose to develop types of hamlets with a system of shared

fences25.

The fact that the practise of common grazing also re-emerged in the enclosed

regime seems to destabilize the initial hypothesis of this study. The principal

purpose was to investigate the co-existence of two parallel agricultural

systems on the plains. However, based on the sources, it can be shown that there was in fact a much more complex

mosaic of competing farming systems, including informal grazing communities and

new hamlets on enclosed land. It is important to consider whether or not these “imperfections” in the reform also caused the problems for enclosure on the plains. If land

surveyors had been more consistent, maybe the reform would have been more of a

success. The material has been crosschecked; individually enclosed farms were

compared to enclosed farms within land-register units. The differences in

economic performance between these two subcategories of enclosed land were

however small and not to the advantage of the individually enclosed farms26.

From this perspective, there is reason to consider another point of view. The

fact that farmers chose to re-establish part of the old regime within the new

strongly suggests that they considered this to be the best way of conducting

farming on the plains. The inconsistencies in the implementation of the reform

were thus a rational response to its shortcomings.

However, over time, the forces incentivising a more fundamental agrarian change

were gradually strengthened. The population grew continuously, and most of this

increase occurred within society’s landless segments (Gadd, 1983: 76-87). This development facilitated

work-intensive investments such as ditching. At the same time, better transport

and credit institutions made markets and capital more accessible.

Ultimately, it was the economic boom of the 1850-70s, fed by the Crimean War and

the subsequent export of oats to England that provided the stimulus for a major

change in farming techniques in the region. This shift included the

introduction of convertible husbandry, as well as heavy investments in

ditching. Once the land was drained, a new and more efficient type of iron

plough was also adopted. Together, these improvements enabled local farmers to

master the heavy clay soils without fallow. Finally, the problem of fencing was

solved by tethering or shepherding the animals27. The use of fences was almost completely given up, an ingenious but also rather

inconvenient solution28.

In this way a new farming regime was finally established, based on the pillars

of enclosure, convertible husbandry, ditches and fenceless farming. The point

is, however, that this defining moment did not come until the process of

enclosure was already almost completed. For the first 45-50 years of the

agricultural systems’ parallel existence, this new farming regime was still not available as a

realistic alternative to the freeholders on the plains.

10. The political economy of enclosures and open fields

In the following, the theoretical aspects of the investigation and the

underlying logic of the systems’ parallel existence will be considered and discussed. This will be done by

contrasting the findings regarding land productivity, such as seeds (Figure 4)

and animal values (Figure 8), with the findings regarding market value for land

(Figure 3) within the two property regimes. Three distinctive periods can be

discerned:

a) The period up until the early 1830s, when enclosed land was traded at equal

or lower prices than open-field land and showed indicators of land productivity

at like levels.

b) The period from the early 1830s until the early 1850s, when enclosed land was

traded at substantially higher prices while production remained similar.

c) The period from the early 1850s, when enclosed land had also gained an

advantage in terms of production.

In the first period, freeholders had few reasons to opt for an enclosure.

Agricultural production was not greater on enclosed land, which in practice

meant that the resources spent on the reform offered no returns. Neither did

the agricultural land market offset the costs of the reform. Enclosure was in

both these respects a sunk investment.

It must have been clear to freeholders from early on that enclosure was a risky

business. Accordingly, up until the mid-1830s, most enclosures were initiated

by noble landlords, merchants from the cities, or state officials who held

crown land as part of their salary29. In many cases, these enclosures were probably formed with the intention of

creating modern, large-scale agrarian enterprises in the English fashion. Given

the fact that the relative costs for fencing decreased with the increased size

of the holding, and also considering the potential re-distributional effects if

former peasant tenants were replaced by landless wage labourers as a part of

the reform, such projects might also have enjoyed reasonable prospects of

success. As long as it was legally possible (prior to 1827), these initiatives

sometimes resulted in partial enclosures in which the applicant’s land was removed from the common fields, but usually whole villages were

dragged into the process, on some occasions against the expressed will of the

peasant landowners. From the example of the transition in neighbouring villages that have ended up

in a highly precarious situation considering the costly maintenance of the

fences, we foresee our ruin, claimed the 40 freeholders in the village of Jung in 1825 to the land

surveyor, who had been appointed by the absent noble landlord who owned

one-fifth of the village30. Evidently, some freeholders also initiated enclosure; according to the law,

each and every one of them had the right to do so. However, only a dozen of the

approximately 3-4,000 freeholders in the area studied did so in the first 30

years of enclosure legislation31.

By the mid-1830s, the economics of enclosure had changed with regards to one

central aspect: a higher land value now compensated for the cost of the reform.

On the other hand, enclosed land was still not more productive than open-field

land in terms of grain or livestock, which in fact makes it somewhat difficult

to explain why this category of land was now more expensive. There is no reason

to believe that, for example, labour productivity within the two regimes had

changed dramatically by this time. Instead, another factor had changed, namely

the expectations regarding the future. The fact that open-field land was now traded at lower prices –despite it being just as productive as enclosed land– supports the assessment that a situation had arisen in which the enclosure of

the remaining open-field villages was regarded as being inevitable in the long

run –or at least so likely that nobody was willing to pay for open-field bound

capital. This type of capital had thus become sunk capital.

Another way to express this supposition is that that open-field land was cheaper

since its buyers would have also had to bear the costs of a forthcoming

enclosure. From this perspective, the price difference between enclosed and

open-field land after 1840 should, in fact, equal the market’s evaluation of the costs of the reform.

Under these conditions, enclosure remained an uncertain project. Even if the

cost of the investment was now offset by the land market, it did still not

yield any higher output from the land. It was in this respect still a sunk investment. Consequently, it was still rational for landowners not to enclose.

Nevertheless, at this point, the period of the systems’ parallel existence now approached its end. From 1838 onwards, new villages

entered the process of dissolving the open fields every year. In contrast to

the early phase, most enclosures were now initiated by freeholders. What did

these farmers expect to win from enclosure if land productivity was not higher

than in the old regime? If open fields were still the most rational option, why

did they not endure?

In order to answer these questions, it is necessary to distinguish between the

aggregate and individual level, and between long and short-term perspectives.

Even if enclosures were not rational in general, they might have in fact been

regarded as rational by individual landowners. With access to capital and with

a bit of strategic behaviour or luck in the partition of the land, enclosure

might indeed have been fruitful in individual cases. In addition, it was this

individual level that counted since according to the absolute priority of

enclosure, every landowner had the right to initiate the process. Some of these

applicants might also have been forerunners in the shift to new farming

technology, experimenting with convertible husbandry before it was generally

considered viable.

Central in this context were prospects for the future. Evidently, the old order

was gradually breaking down. When neighbouring villages were enclosed, common

grazing of livestock over village boundaries was no longer possible. In these

cases, villagers in the open-field villages had to share the costs of building

and maintaining the fences that were erected on previously open borders. In

addition, the two-field system was getting increasingly clumsy. By the 18th century, peas were being cultivated within temporary fences on fallow land.

Towards the middle of the 19th century, winter rye, potatoes, and probably, on some farms, clover were sown in

a similar manner. The system still prevailed –but would it support future developments? Furthermore, the time horizon of

investments was crucial to the farmers’ evaluation of the situation; they might have wanted to erect new buildings or

drain the wet clay soils. All such investments ran, from the perspective of a

possible future enclosure, the risk of becoming sunk investments. In order to

have a secure investment time horizon, the foresighted and forward-looking

farmer needed to enclose.

In addition, also the fact that the real estate value of open-field land had

been downgraded must have put pressure on the old regime. This fact could be

ignored on farms where there was a future prospect of continuity in farming

within the household. In the case of a freeholder who planned to sell his land

however, the situation was different. In practice, he then had to bear the

costs of enclosure, as his land was now worth less –even if he and his fellow villagers had chosen to stay out of the enclosure

process. From this perspective, the alternative cost of actually implementing an enclosure was zero.

In several ways, the prospects of future enclosures were thus also the driving force behind the actual implementations of

enclosures. As demonstrated earlier, these prospects were not yet based on the

enclosed regime’s supposed economic superiority. They were based on institutional arrangements,

most notably the absolute priority of enclosure, which, in the long run, made

the reform almost inevitable.

For the village as an institution, the absolute priority of enclosure meant that

it faced a situation in which the veto of a fellow villager could end its

existence. Every quarrel over, for example, demarcation lines between strips of

land, every dissatisfaction with common decisions to do with grazing or fences,

every antagonism or misunderstanding at the personal level threatened to

escalate, which could destroy the whole village. Anyone who owned a piece of

land in the village could use the threat of enclosure to blackmail or demand

special privileges, such as the right to temporarily enclose parts of the open

fields. The power of the collective could in every instance be trumped by the

will of the individual. Unanimity was required if the village was to endure.

From this perspective we could just as well pose the question the other way

around: How did such institutions survive for so long? Considering the size of

many villages on the plains, the situation must have been highly unwieldy and

unpredictable. In both Öttum and Storvånga, there were 80 individual landowners. Land was bought and sold, new

stakeholders entered the communities, people grew old or died, and new personal

relations and government structures had to be established. Yet, in these two

villages, it took until 1849 and 1850, respectively, until a general enclosure

was finally initiated. It must have taken the force of a very strong common

incentive which bound the villagers together for the village institution to

survive for so long. This common incentive was not based on a cultural preference for village life and traditional farming. It was

based on the basic fact that enclosure did not yet offset its cost for the vast

majority of villagers. New villagers entering the community bought their land

at a reduced price; they had made a good deal –until that very moment when a fellow villager applied for enclosure.

There are a few, interesting examples of how villagers handled this risk. In

1844, the 45 villagers of Längjum set up a mutual contract. It stated that the individual who applied for

enclosure would bear the full cost of the reform, including for the rest of the

villagers32. In other cases, there are examples of peer pressure that, if the common will

of the community was still being ignored, could evolve into threats or even

violence. In Edsvära, the fruit trees and carriages of the applicant were supposedly destroyed as

a warning33. In Fyrunga, things got even further out of control. The person who applied for

enclosure was the object of intimidation, derision, and eager persuasion in an

attempt to force him to withdraw his application. In the end, an angry mob of

fellow villagers chased him down to the river where he, in a failed attempt to

get safely over to the other side, drowned. Local tradition in Öttum tells a different story; the applicant (an outsider) is supposed to have

used the threat of enclosure as a form of speculation and was bought out with a

considerable amount of money. In this way, open fields survived for another few

years. The situation can be compared to the English case in which bribes and

intimidation were used in order to convince reluctant stakeholders to participate in the reform so that the required unanimity (in the pre-parliamentary

situation) or qualified majority (parliamentary situation) could be achieved.

On the plains of western Sweden, it was the other way around; bribes and

intimidation were used to make eager stakeholders refrain from exercising their right to enclose, so that the open fields would continue

to exist.

In conclusion, it can be seen how the villagers were trapped by the

contradictions of the systems’ parallel existence. Villagers were trapped between the old, open-field bound

capital as sunk capital and enclosure as a sunk investment; between the common

endeavour to avoid enclosure and the individual right to veto this endeavour;

and between a stubborn defence of the old order and a growing awareness that

this order would not prevail.

It was not until the 1850s and the adoption of a new farming regime based on

convertible husbandry, ditching, and tethering that this contradictory

situation came to an end. In light of the new prospects that were rapidly

opening up, previously reluctant freeholders could now embrace enclosures as

one of the pillars of their growing prosperity. It should likewise be noted

that the pioneers of the reform were not its winners. The true victors of this

transition were actually the farmers who managed to avoid enclosures up until the 1850s and who could make a direct leap from open-field

farming to tethering and convertible husbandry on enclosed land. In this way,

the period in which enclosures did not offer any financial gain was avoided, as

were the heavy investments in fences, which had long been associated with the

reform. With the advancement of the new fenceless farming regime, such

enclosure-bound capital now increasingly became sunk capital.

11. Conclusions

One of the contradictions of enclosures is how they both promoted and threatened

property rights. The aim of the reforms was to establish modern, uncontested

land-ownership. In order to realise this ambition, however, existing property

rights had to be demolished.

Legislators in Europe tackled this dilemma in different ways. At one extreme is

the situation in pre-parliamentary England or in 19th century France, where unanimity among landowners was required for a reform.

During English parliamentary enclosures and in several 19th century German states, a qualified majority was considered enough34. At the other extreme is the Swedish laga skifte legislation, where it only took a petition from one stakeholder to enclose a

village.

In this study, the parallel existence of enclosed and open-field land systems on

the plains of Västergötland provides the starting point for a discussion on the economic and

institutional mechanisms of Swedish enclosures. The first villages in this area

were enclosed in 1805, and the last ones in the 1860s. The fact that the two

systems coexisted during half a century enables us to examine source materials

such as probate inventories and registers of land sales in order to reconstruct

the farming practices, production, and land values that existed within the two

regimes, using the area as an “historical laboratory” of enclosures and open fields. At the same time, the period of parallel

existence has also been a discrete object of inquiry. Given the fact that

villages in the area were big (up to 80 farmsteads), how could open fields have

survived for so long in a situation where every landowner could veto their

existence?

This investigation has shown that the main explanation for the slow acceptance

of reform was that it offered few advantages for farmers on the plains.

Productivity was not higher on enclosed land than on the open fields, and there

were no dynamic technological effects coupled with the reform. Commonly, the

traditional two-field system was re-established after enclosure, sometimes even

including elements of common grazing. These practices indicate that the old

regime was still widely considered to be the best way of conducting farming on

the plains. From this perspective, it was above all strong institutional

imperatives that drove the reform process forward.

Evidence from the land market offers a complementary outlook on these

developments. During the initial phase of the studied period, enclosed land was

traded at lower prices than open field land. Given the costs of the reform,

this was a discouraging pattern. From the 1830s, however, the situation was

reversed; now, the land value of open fields lagged behind. As land

productivity within the two regimes was at similar levels, the most probable

explanation for this divergence is that buyers were no longer willing to pay

for old open-field bounded capital, given the high probability of enclosure. It

was not until the 1850s that major shifts in farming technology finally took

place within the enclosed regime, including a shift from the two-field system

to convertible husbandry and a rapid increase in cereal production. This was

almost a half century since the first enclosures on the plains.

While recent Swedish research largely portrays the country’s course of enclosures as a great success, the more complex understanding of the

process outlined in this article agrees to some extent with studies of other

countries, which contest the alleged superiority of the enclosed regime35. It must nonetheless be noted that, although the effects of enclosures in the

study area long remained limited, the reform was still a necessary precondition

for the post-1850 agrarian take-off.

One critical question that this article has not been able to fully answer is why

this turning point did not come earlier. One problem was that high costs for

fences combined with the hard-worked clay soils hampered the introduction of

convertible husbandry. Reasonably, the agrarian take-off depended on a whole

set of interconnected factors, including aspects of technology as well as

access to labour, markets, and capital. Enclosure was part of that picture –but it could not alone initiate a change.

The transition to a modern farming regime was not as complicated everywhere in

Sweden. The cradle and the showroom of Swedish enclosures was the southernmost

province of Scania. Starting on the Söderslätt plains, both enclosures and convertible husbandry rapidly spread over the

province during the first decades of the 19th century. Why was the reform so successful in this area and not on the Västergötland plains? Hopefully, future research can provide an answer. The fact that

the best-yielding agrarian districts in the country are in the south must

however have been one strategic factor; the Söderslätt plains, where the reform first took off, possess some of the most fertile

soils in Europe. With higher yields, surplus production was larger, which in

its turn stimulated market integration –all these factors must have been crucial in pushing the region towards

enclosure. In addition, soils in the south are comparably light, which

facilitated the introduction of convertible husbandry36.

Once the reform expanded beyond this core area, it had declining success. On the

vast and heavy clay plains in Östergötland and the Malar Valley enclosures and convertible husbandry did not gain

momentum until the 1850-80s, and the same is true for most woodland areas in

the country37. In these regions, villages were smaller than on the Västergötland plains, which probably made it easier for the villagers to manage the

uncertainties of enclosure. Still, the basic political economy of enclosure

must have closely resembled the one described in this study, with strong

institutions promoting a reform that most farmers did not yet consider

economically viable.

In terms of a broader European context, the contrasts with the classical English

case of enclosures should finally be considered. While in England, unanimity

(in the pre-parliamentary situation) or a qualified majority (during

parliamentary enclosures) was required to enclose land, in Sweden during laga skifte, unanimity was in fact required to avoid enclosure. And while the institutional

situation in England probably delayed enclosures that were rational from the

large-scale landowners’ perspective, the reversed Swedish institutional situation seems to have

hastened enclosures in a situation when open fields were still more rational

from the free holders’ point of view.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Klas Dahlén and Linus Karlsson for archival support, Sara Ellis Nilsson and Rachel Pierce

for language editing, Ole Aslaksen for GIS assistance, and the three anonymous

reviewers of Historia Agraria for helpful comments on the manuscript. Earlier versions of the work were

presented at the Permanent European Conference on the Study of Rural Landscapes

in Gothenburg in 2014 and at Rural History in Girona in 2015. We are thankful

for the comments put forward during these conferences. Ekmansstiftelserna and Västergötlands Fornminnesförening supported this research.

REFERENCES

Åberg, A. (1953). När byarna sprängdes. Stockholm: LT.

Allen, R. C. (1982). The Efficiency and Distributional Consequences of Eighteenth Century

Enclosures. The Economic Journal, 92 (368), 937-53.

Allen, R. C. (1992). Enclosure and the Yeoman: The Agricultural Development of the South Midlands,

1450-1850. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arrhenius, J. P. (1848). Berättelse öfver förhandlingarne vid det andra Allmänna svenska landtbruksmötet i Stockholm 1847. Stockholm.

Beltrán, F. J. (2016). Common Lands and Economic Development in Spain. Revista de Historia Económica-Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History, 34 (1), 111-33.

Carter, P. (1998). Enclosure Resistance in Middlesex, 1656-1889: A Study of Common Right Assertion. PhD thesis. London: Middlesex University.

Chapman, J. & Seeliger, S. (2001). Enclosure, Environment & Landscape in Southern England. Stroud: Tempus.

Clark, G. (1998). Commons Sense: Common Property Rights, Efficiency, and Institutional

Change. The Journal of Economic History, 58 (1), 73-102.

Dahlman, C. J. (1980). The Open Field System and beyond: A Property Rights Analysis of an Economic

Institution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dyer, C.C., Thoen, E. & Williamson, T. (Eds.) (2018). Peasants and their Fields: The Rationale of Open-Field

Agriculture, c. 700-1800. Turnhout: Brepols.

Edvinsson, R. & Söderberg, J. (2011). A Consumer Price Index for Sweden 1290-2008. Review of Income and Wealth, 57 (2), 270-92. (Price index available at

).

Gadd, C. J. (1980). Swedish Probate Inventories, 1750-1860. In A. van der Woude & A. Schuurman (Eds.), Probate Inventories: A New Source for the Historical Study of Wealth, Material

Culture and Agricultural Development. Wageningen: Afdeling Agrarische geschiedenis-Landbouwhogeschool.

Gadd, C. J. (1983). Järn och potatis: Jordbruk, teknik och social omvandling i Skaraborgs län 1750-1860. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

Gadd, C. J. (1998). Jordbruksteknisk förändring i Sverige under 1700- och 1800-talen: Regionala aspekter. In L. A. Palm, C. J. Gadd & L. Nyström (Eds.), Ett föränderligt agrarsamhälle: Västsverige i jämförande belysning. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

Gadd, C. J. (2011). The Agricultural Revolution in Sweden, 1700-1870. In J. Myrdal & M. Morell (Eds.), The Agrarian History of Sweden. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

Grantham, G. W. (1980). The Persistence of Open-Field Farming in Nineteenth-Century France. The Journal of Economic History, 40 (3), 515-31.

Grüne, N., Hübner, J. & Siegl, G. (Eds.) (2016). Rural Commons: Collective Use of Resources in the European Agrarian Economy. Inssbruck: Studien.

Hansson, B. (1992). How the Land is Used. In Å. Clason & B. Granström (Eds.), National Atlas of Sweden: Agriculture. Stockholm: SNA.

Healey, J. (2016). Co-operation and Conflict: Politics, Institutions and the Management of

English Commons, 1500-1700. In N. Grüne, J. Hübner & G. Siegl (Eds.) Rural Commons: Collective Use of Resources in the European Agrarian Economy. Inssbrug: Studien.

Heckscher, E. F. (1941). Svenskt arbete och liv: Från medeltiden till nutiden. Stockholm: Bonnier.

Helmfrid, S. (1961). The Storskifte, Enskifte and Laga Skifte in Sweden: General Features. Geografiska Annaler, 43 (1-2), 114-29.

Hoffman, P. T. (1989). Institutions and Agriculture in Old-Régime: France. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft,145 (1),166-81.

Jansson, U. (1998). Odlingssystem i Vänerområdet: En studie av tidigmodernt jordbruk i Västsverige. PhD thesis. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

McCloskey, D. N. (1975). The Economics of Enclosure: A Market Analysis. In W. N. Parker & E. L. Jones (Eds.), European Peasants and Their Markets: Essays in Agrarian Economic History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Moor, T. de (2009). Avoiding Tragedies: A Flemish Common and Its Commoners under the

Pressure of Social and Economic Change during the Eighteenth Century. Economic History Review, 62 (1), 1-22.

Nyström, L. (2007). Att göra omelett utan att slå sönder ägg: Skiftesvitsordets teori och praktik: laga skifte i Fyrunga 1844. In L. A. Palm & M. Sjöberg (Eds.), Historia: Vänbok till Christer Winberg. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

Olsson, M. & Svensson P. (2010). Agricultural growth and institutions: Sweden, 1700-1860. European Review of Economic History, 14 (2), 275-304.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pettersson, R. (1983). Laga skifte i Hallands län, 1827-1876: Förändring mellan regeltvång och handlingsfrihet. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

Pettersson, R. (2003). Ett reformverk under omprövning: Skifteslagstiftningens förändringar under första hälften av 1800-talet. Stockholm: Kungliga Skogs- och Lantbruksakademien.

Renes, H. (2010). Grainlands: The Landscape of Open Fields in a European Perspective. Landscape History, 31 (2), 37-70.

Shaw-Taylor, L. (2001). Labourers, Cows, Common Rights and Parliamentary Enclosure: The

Evidence of Contemporary Comment c. 1760-1810. Past & Present, 171 (1), 95-126.

Skaraborgs Läns hushållnings sällskaps tidning (1852). Skara: Skaraborgs läns hushållningssällskap.

Svensson, H. (2005). Öppna och slutna rum: Enskiftet och de utsattas geografi: Husmän, bönder och gods på den skånska landsbygden under 1800-talets första hälft. Lund: Lunds universitet.

Svensson, P. (2006). Peasants and Entrepreneurship in the Nineteenth-Century Agricultural

Transformation of Sweden. Social Science History, 30 (3), 387-429.

Söderström, M. & Piikki, K. (2016). Digitala åkermarkskartan: Detaljerad kartering av textur i åkermarkens matjord. Skara: Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet. (Interactive soil texture map available

at

)

Thompson, E. P. (1963). The Making of the English Working Class. London: Gollancz.

Turner, M. E. (1980). English Parliamentary Enclosure: Its Historical Geography and Economic History. Folkestone: Archon Books.

Wiking-Faria, P. (2009). Freden, friköpen och järnplogarna: Drivkrafter och förändringsprocesser under den agrara revolutionen i Halland, 1700-1900. PhD thesis. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

Winberg, C. (1990). Another Route to Modern Society: The Advancement of the Swedish

Peasantry. In M. Lundahl & T. Svensson (Eds.), Agrarian Society in History: Essays in Honour of Magnus Mörner. London: Routledge.

Yelling, J. A. (1977). Common Field and Enclosure in England, 1450-1850. London: MacMillan.

NOTAS A PIE DE PÁGINA / FOOTNOTES